I should add a codicil here. I had always assumed that my advice on the measure necessary to get rid of the faults in the piping of the intake and exit from the air pump had been ignored as it meant installing a tank to act as a lodge in the cellar beneath the engine and the museum carpentry department who were using it as a workshop refused to play ball. Later I found out that Michael Wright, the man in charge had recognised that I was right and had fought long and hard for the modifications. I am not sure whether, in the end, he succeeded. See

THIS Entry in Wikipedia and note the work he did later on the Antikythera mechanism which is a triumph in its own right. I do know that other factors came into play and internal politics played a big role but I am keeping quiet about that, it involves people who are still alive and I am not interested in raking old matters up. Back to Ellenroad!

AUSTRALIAN DIVERSION

By the autumn 1986 it became obvious that the Environmental Health Department of the council wanted control of the whole asbestos removal contract. There was little doubt that their method would be the most expensive but on the other hand, it would be thorough and they would carry the responsibility. On the whole it was a good thing for me and I laid back and accepted it. There was another reason for off-loading the whole exercise on to the council, Mary and I had a trip to Australia planned and father’s ashes were going back home. But that's another story!

ELLENROAD FUNDING

The Ellenroad Project as it had become known was functioning well by the beginning of 1986. I had obtained enough initial funding and manpower to press on with my programme and could devote some serious time to yet more fund-raising. The first thing to say is that I didn’t raise all the funds for the project. Alan Brett and Andrew Underdown, the local councillors and John Pierce were instrumental in obtaining funds, or triggering me off to approach funders that were local. I dealt with day to day matters on site and all the private sector and central government funding. It might be helpful here if I told you what my basic approach was.

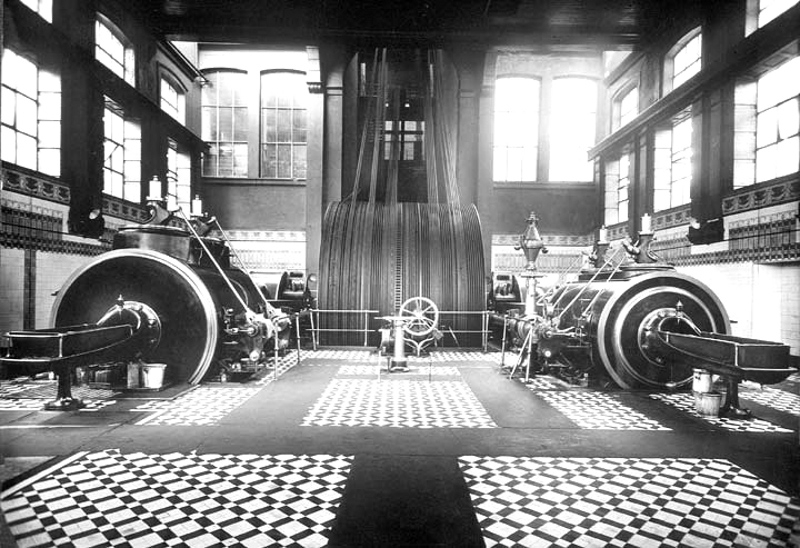

The first thing to recognise is that if you are seeking funding from any source the most important thing to start with is a good cause. This sounds simplistic but is at the root of the matter. Ellenroad was a worthy case, it had so much going for it. It was the last large steam textile mill engine in its original house with all its artefacts intact and was so sited that it had a good catchment area. Because of the proximity to the motorway network, if you drew the isochrones for Ellenroad on the map, (these are lines showing travelling times) the 1 ½ hour line enclosed an area with a population of over 15 million people, one of the best ride times in Europe. In order to support this case you have to have clear objectives, a well worked out and costed overall plan and separate, clearly identifiable segments of that plan which you can cost accurately, give proper time scales for and use these as the basis for funding applications. Funding bodies like to have a menu. They also like to feel that whoever is applying the for the funding is in complete control, both by knowledge of the project and familiarity with all the technologies involved.

The next principle to grasp is that funding is almost always plural, in other words a partnership between the Trust and a number of funders for one segment. The most important funding in this segment is that which the Trust brings to the table which is the result of its own efforts. In other words, funds raised by volunteers dedicated to helping the project. A few hundred quid from jumble sales can trigger off tens of thousands, funders need to know there is local support

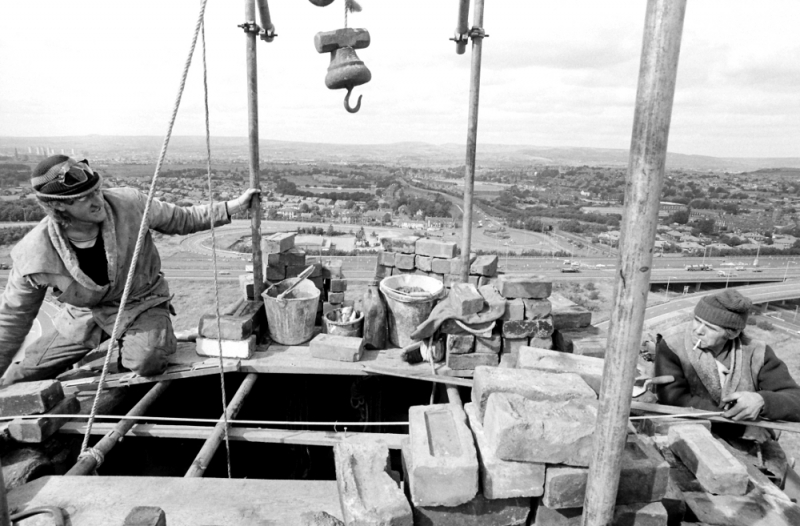

The next important thing to realise is that funders are in the business of giving money away. They are never happier than when they are handing out large cheques. The faster they can do this, the sooner they can get out on to the golf course! So, the essential thing you have to do is to persuade them that you are kosher. The best way to do this is to be able to show that one of the funders is so prestigious as to be a guarantee to all the other participants. I tackled this one early on and decided that apart from English Heritage who were high prestige but almost duty bound to fund, we needed something special. I remembered the National Heritage Memorial Fund which was initially funded after the war from the sale of war surplus goods. In later years it became the funder of last resort for national treasures or works of high art which, if not bought by a museum, would leave the country. The only industrial artefact they had ever funded to my knowledge was Clevedon Pier and I think there were some quite serious problems with that. When I approached them and invited the acting Director to come up and see what we were doing I was flying a kite. He came, he saw, we conquered! They became 25% funders of the main structural elements of the project like the back wall, the chimney and big refurbishing jobs on the structure of the engine house itself. The ability to say that you were funded 75% by EH and NHMF was probably the best commendation any segment of the project could have.

The next most important attribute that attracts funders is success. If you can reel off details of total cost of project, proportion funded in say three years and then give menu of projects left to accomplish you excite people and they want to be associated with success. A concomitant of this is the fact that you have to demonstrate that you are keeping the momentum, that the overall project is rolling forward like a juggernaut. This internal dynamism is a most valuable asset and generates confidence and funding at the same time. It is most damaging if the impetus is lost for any reason. A classic example was the failure of Pennine Heritage at Queen Street Mill, this was a tremendous set-back for that project and has never been entirely overcome. Strangely enough, the most likely source of loss of momentum is not some unforeseen need for funding, like the second asbestos clearance at Ellenroad but internal schisms in the management structure of the organisation. This is the reason why it is essential to get the management structure and responsibilities clear at the outset. Even with all this in place there is no guarantee that problems won’t be generated internally.

There was a case in point at Ellenroad. I was always on the lookout for new talent. People with special skills who we could co-opt into the organisation to give us the benefit of their specialist knowledge. Early in 1987 I found such a man, Ray Colley. He was a retired TV executive who was living in Rochdale who was looking for fresh fields to conquer. We approached him and he came to help as a volunteer, sitting on several committees and generally being a useful adjunct to the organisation. I can’t say that I got on well with him, he was a little too abrupt for my liking but there was nothing that said we had to like each other, just that we got on with our jobs.

Earlier on, I had head-hunted another volunteer, Horace Longden. I needed someone to act as chairman of the Friends Organisation I wanted to found to provide the cadre of volunteers to actually run the engine eventually. This was a major stone in the foundations of the project because, in effect, because of the way I had written the Articles of Agreement of the Trust separate from the organisation of the Friends, the Friends would actually run the enterprise and the Board of Directors only control was over the broad policy, major funding and the Project Manager who was the buffer between the Friends and the Board. I tried twice to get the Friends off the ground and failed. It wasn’t until I got Horace to have a go and I stepped back that it succeeded. I was the wrong person for the job and it took two failures to convince me! Slow learner again.

Horace was a star, a gem and one of the most perfect gentlemen I have ever been privileged to meet. He was totally reliable, always absolutely correct and one of the most able organisers I have ever seen in action. His forte was people, he understood them far better than I and his management style was the epitome of the iron fist in the velvet glove. Indeed, the glove was so velvet that a lot of people who know him would not recognise that description. If Horace decided that a principle was involved he was a force to be reckoned with. By 1987 he was chairman of the Board of Directors at Ellenroad and I used to wonder at the members of the committee who mistook his measured and low key style for bumbling. I had no control over the Directors and wondered at times about some of them.

Back to 1987. I think it was sometime in summer, July perhaps, I got word that there was a move afoot to remove a lot of my power, reduce my wage and install Ray Colley as Project Manager. My attitude was that I didn’t want to play this game, if the directors were so disloyal, or dissatisfied with my work that they wanted me out that was up to them. I wasn’t going to argue because I had achieved my main objective, I had saved the Ellenroad Engine and made sure the buildings were stable. I was sure I had a lot left to contribute but I wasn’t going to go into a decline if they took that away from me.

I always attended the Board meetings to make my reports and give advice. Horace asked me to go up to see him on the day of the meeting. I went round to his house and he told me exactly what was going to happen. He said that Gavin Bone was going to back a motion that would result in me taking a back seat at a reduced salary and Ray Colley was going to be proposed in my place. I told Horace what my attitude was, I wasn’t interested, if they wanted me out I would go but there would be no back seat driving. My assessment was that what they were after was the job and the salary, they wanted me to stay on to do the same work I had done all along at a lower wage. Forget it! Horace gave me a long lecture about strategy and told me that I had to keep my temper and leave it up to him. I trusted him so I left it entirely in his hands.

The Board Meetings were held in the Gothic splendour of Rochdale Town Hall, a wonderful building designed by the same architect as the House of Commons and having possibly more wood panelling and encaustic tiles to the square foot than Parliament! Very soon after the meeting started Horace announced that a motion was proposed which affected my position and asked me to withdraw. I left and went for a beer in the Flying Horse, a nearby pub. After about half an hour I was asked back in and my new terms were announced, I was to get slightly more money and all my powers were left intact. Ray Colley was offered a minor role at a small salary but I think he eventually refused it. Later I asked Horace why he had backed me, he said he thought I was too passionate and headstrong to be a good manager in normal circumstances but the evidence was that it was these characteristics that had brought Ellenroad so far so fast. He also doubted if anyone else had the funding contacts and the basic knowledge of steam engines. I took this as a vote of confidence and carried on but after that I always watched my back. As for my mate Gavin Bone, I crossed him off the Christmas Card list and managed without the benefit of his company.

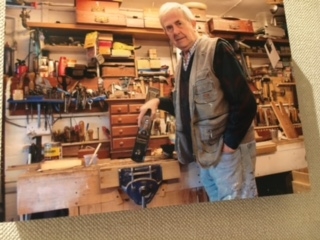

Horace Longden with the Mayor at Ellenroad in the early days. He was a lovely bloke and just the right man for the Friends.