During 1978 I was asked to advise English Heritage and Quarry Bank at Styal on the removal of a large water wheel from Glass Houses near Pately Bridge. I have no inflated ideas about my importance to them as an expert, I think my sole function was to be someone prepared to write a report recommending the removal so that if there was any criticism I could be the fall guy. I recommended Brown and Pickles for the job and they got it. Newton told me later that this was the job that persuaded them it was time to retire gracefully because when they hit trouble dismantling the old wheel they were refused any extra payments and lost money on the job. This wasn’t a financial disaster but it knocked the heart out of Walt and Newton. I always felt bad about having landed them with that one.

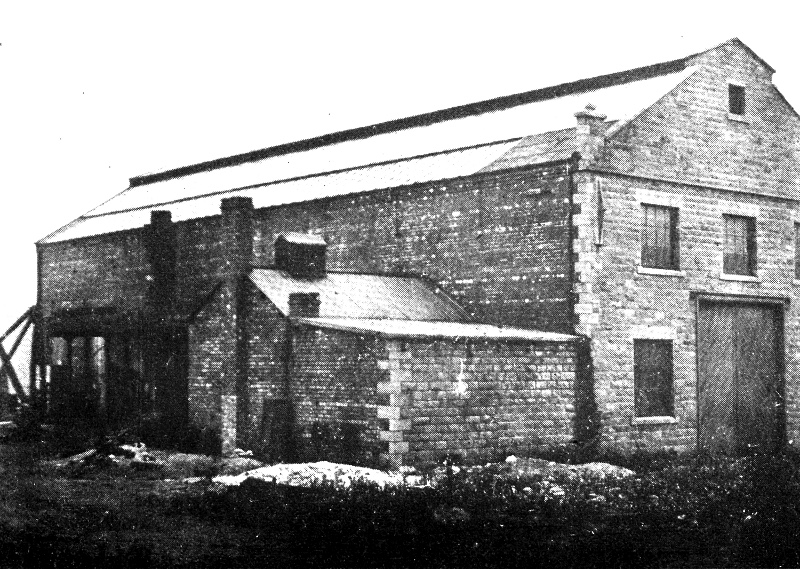

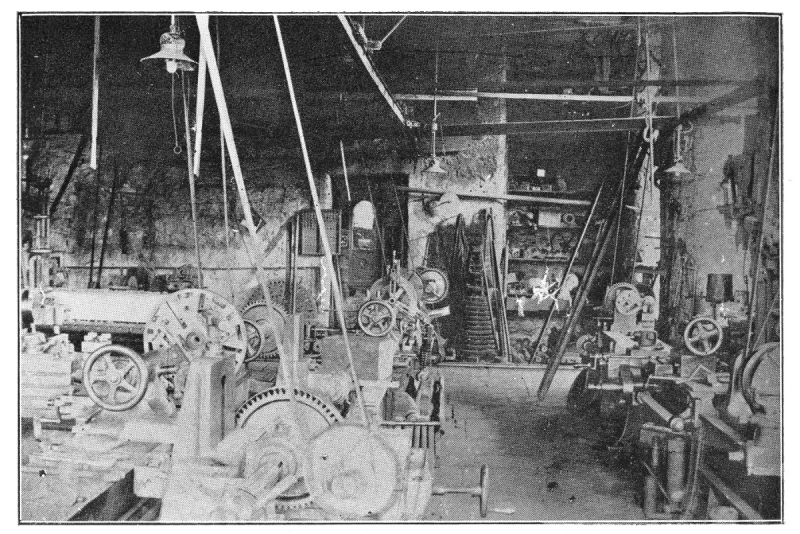

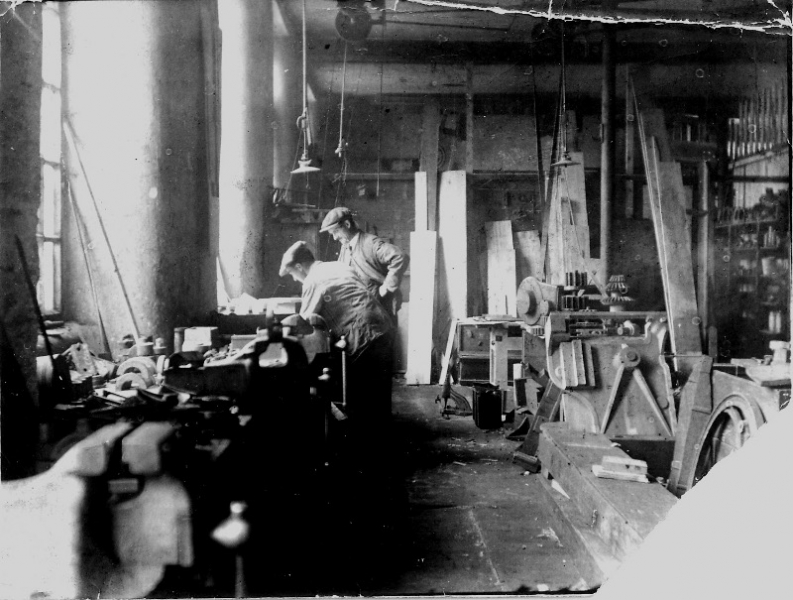

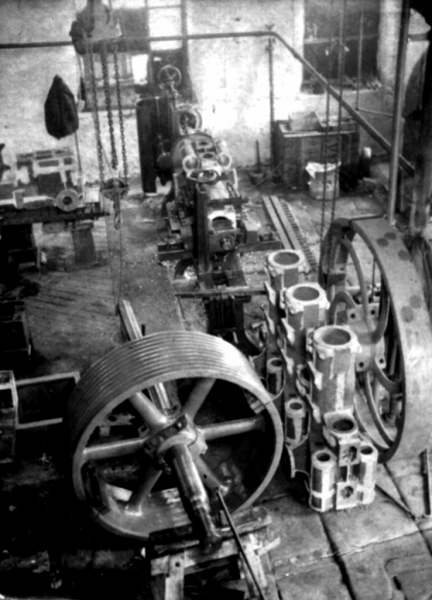

On the 10th of May 1981 Newton and Walt Fisher sold out to Gissing and Lonsdale who have kept the name of the firm alive. The Riley Street clock was flitted across the road to Gissing and Lonsdale’s offices on Wellhouse road and was fitted with two extra dials. Up to 1988 it was wound manually but on April 4th 1988 it was converted to electric winding. N&R Demolition from Portsmouth Mill at Todmorden moved in and demolished the Wellhouse Machine Shop. It was very sad to see the old buildings come down, so much wonderful work had been done in that old building. I stood with Newton and Olive watching the machines working and remembering tales that Newton had told me about milling gears for his dad when he was fourteen years old with snow blowing under the shop door and collecting round his feet. Him and Jim Fort having competitions to see whose swarf would go furthest down the yard without breaking. The lads waiting until the engine had been running for a while before going out to the tippler toilets in the yard in winter because the exhaust from the engine drains warmed them up. All the skill and memories accumulated over the years blown away by progress. Inevitable I suppose but sad.

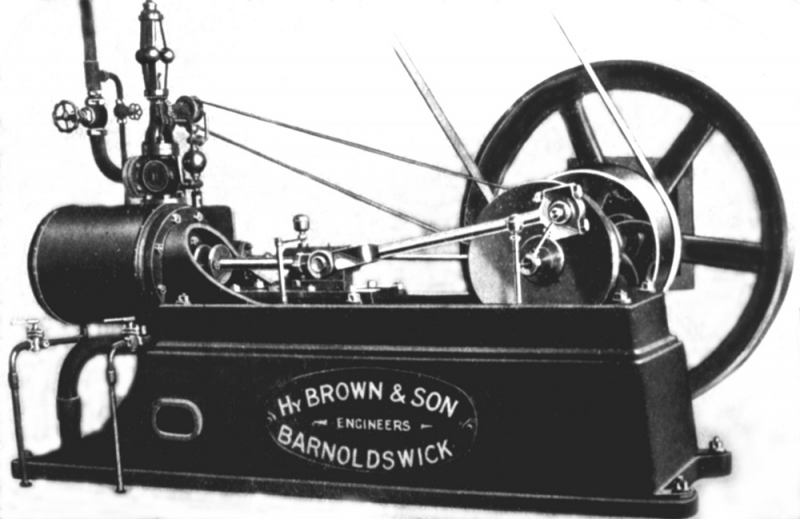

As I have said, I never met Johnny Pickles, I was too busy driving all over the world and parts of Gateshead in the ten years from 1959 to 1969 when it could have happened. I first met Newton when I took over Bancroft engine in 1972 and he taught me all I know about engines and turning. I visited him the day he died to wish him and Beryl a happy new year. I’ve always said that there are two sorts of men in this world, the ones who know but won’t help you and the ones that know and will share their knowledge with you. Newton spent hours in the engine house and workshop with me answering questions and showing me what to do. That sort of skill can’t be found in books because nobody ever wrote it down. That’s one of the reasons why I’m enjoying writing this so much, it lets me share some of Newton with you. Walt Fisher is still alive and well and is 91, whenever I have a query about the old days I just pick the phone up and get the answer off him, long may it continue. Henry Brown Sons and Pickles were an integral part of the history of the steam driven textile industry in the district. The echoes of those early starts in the trade are still with us, Ouzledale Foundry was a large part of the story I have told and they are still a thriving business in the town so we still have a direct link back to 1890 when Henry Watts was making castings on Longfield Lane for Henry Brown. That pleases me.

Here’s the obituary I wrote for the Barnoldswick and Earby Times when Newton died.

NEWTON PICKLES. ENGINEER AND MASTER CRAFTSMAN. BORN 10TH OF MARCH 1916, DIED 1ST OF JANUARY 2001.

Tuesday, 02 January 2001

Yesterday was a quiet day, everyone in Barlick seemed to be recovering from the New Year celebrations. I decided it would be a good day to call in on my old mate Newton and his wife Beryl to wish them a happy New year. I had a cup of tea with them, a good crack with Newton and he pulled my leg because he’d read my last piece about him and me testing the Bancroft engine one Christmas Eve long ago and he reminded me of something I’d forgotten to put in to the article. If you remember, Newton and I were sat in the darkened engine house listening to the engine running like a rice pudding and drinking whisky.

Young John, Newton’s grandson was with us and after a while he got a bit fidgety and said “When are you going to stop this engine?” I said “If it’s getting on your nerves, you stop the bloody thing, you know how!” Me and Newt had a good laugh and John went to stop the engine but he was too short to reach the stop valve and we had to break off from the serious matter of our Christmas drink while we found a buffet for John to stand on. He did it and the engine stopped.

This was typical Newton, he had a memory like a sharp knife and once you triggered him off, he would recount an incident as though it happened yesterday. Even better, as far as a historian is concerned, he would tell you the same story twenty years later in exactly the same detail, he was totally reliable as a witness.

When he’d finished saucing me, we had a good laugh and as I went out he gave me a big hug, unusual behaviour for him. They were getting ready for going out to have a meal and that was the last I saw of him. Beryl rang me this morning to say he had died during the night. I’ve only just remembered that hug, very strange but welcome.

The first thing I want to say about Newton is that knowing how I feel I can make a guess as to how his immediate family are feeling today. There is such a big hole in so many people’s lives this morning and it can’t be filled. Time will heal I know, but nothing anyone can say can make it better. The only thing I have to offer is that the better the person, the bigger the loss, it’s almost as though it is part of the price we have to pay for having someone like Newton in our lives. He was like a father to me and I shall miss him so much.

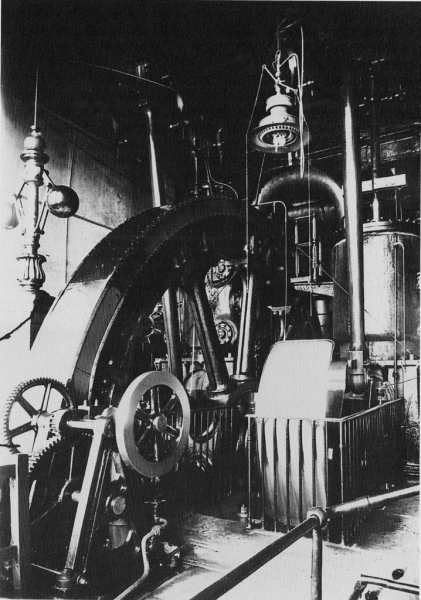

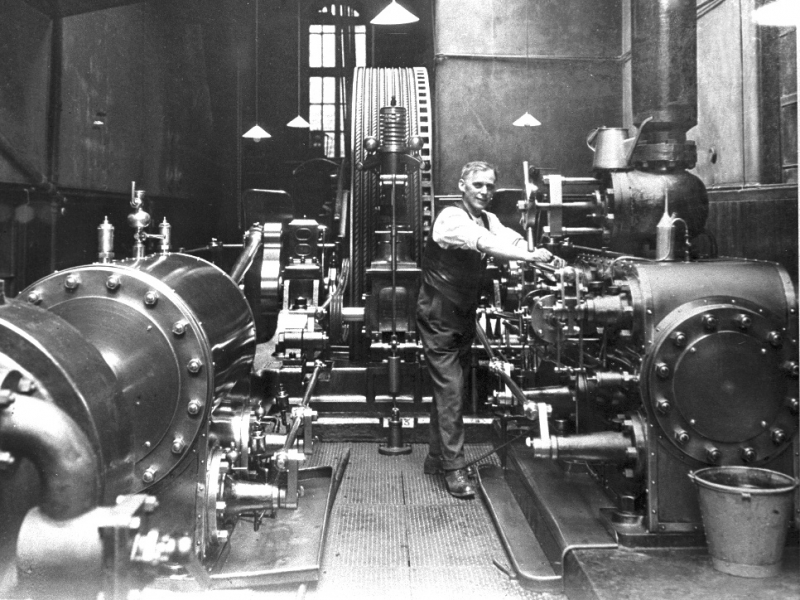

I’d like to tell you something of the Newton I knew and how he affected my life. In 1973 when I took over Bancroft engine I knew I was in for a steep learning curve but comforted myself with the knowledge that it would all be written down somewhere and all I had to do was get the books and read them. I was in for a shock! I soon found out that there was nothing practical written down, plenty about the theory, written by blokes who had never run an engine in their lives but nothing about what you actually did to run an engine.

This was where I had a stroke of luck, I heard about this firm in the town, Henry Brown Sons and Pickles and when I rang them a funny bloke came on the line and when he heard my problem said he’d come up to see me. Now, there are two sorts of people in this world, the ones who reckon they know but won’t tell you and the ones who really do know and will tell you all. Luckily for me, Newton was the latter. I told him my problem and he took me under his wing. From then on it was plain sailing, when I came up against a problem I rang Newt, he came up, sorted me out and pointed out what I ought to be looking into next. I think the proudest day of my life was when he came into the engine house one day, stood there listening to Mary Jane and James for a second or two and then turned round to me, “It’s running better than it ever has since it were put in. Tha wants to be careful, tha’ll mek an engineer yet!”

When Bancroft reached the end of its days Newton was with me in the engine house on the Wednesday afternoon of the week when we anticipated stopping on the Friday. We were making plans for what we would do to the engine to make sure it would be in good condition if anyone wanted to start it up again. We’d had a lot of visitors that week, the word had got round that Bancroft was stopping and people naturally wanted to see it running one last time. Professor Owen Ashmore from Manchester was there and he said he’d just watch the engine stop at dinnertime, he wanted a picture of me doing it. I told him that if I was right, when we stopped at dinnertime it would never run again because the weavers had been paid and I doubted whether they’d come back. That being the case, I wasn’t going to stop it, Newton could do it. I remember Newton protesting but I told him that the job was his. It was the last Barlick engine and he’d looked after all of them, he could kill the last one. He did, and I have a picture of him doing it. It seemed fitting that he should preside over the end of steam in Barlick. We cheated of course, we banked the boiler and the following day Newton and I ran the engine one last time while we flooded it with oil and I stopped it after that.

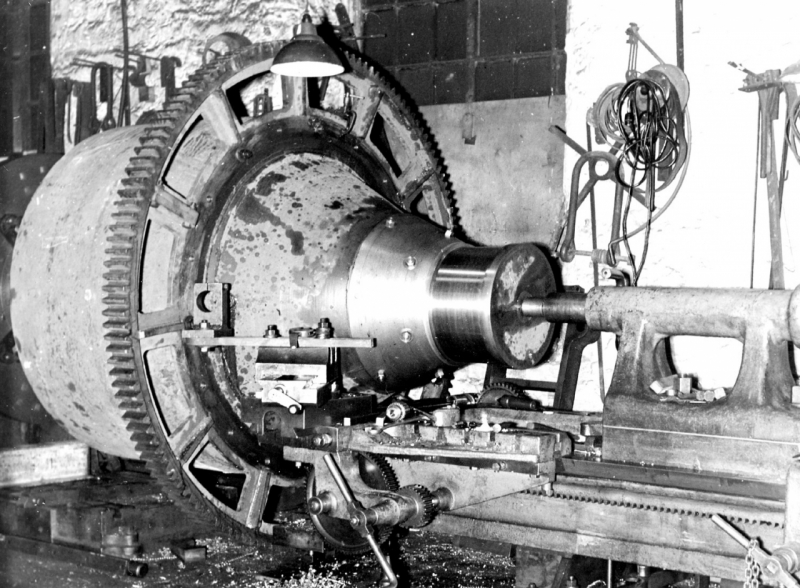

In 1987 Newton was in a poor way. He had nursed his second wife Olive through cancer and was very low. I went to a foundry I knew and got some castings made for a couple of steam engines. I took one set round to him at Vicarage road and told him I wanted him to make me into a turner. He had to make an engine out of the castings and I’d do the other set. Six months later he had an engine, I had made mine and had it passed by Pickles and shortly afterwards he met Beryl and started another very happy period of his life.

So there you are, that’s my version of Newton Pickles, a funny old bugger but the best teacher and friend a bloke could have. I owe everything I know about engines and machining to him and will never forget his generosity and support when I needed it most. There’s lots more to tell about him but I shall be telling the stories for many years yet. My thoughts go out to Beryl and the family, I have lost a friend, their loss is greater than mine. One last word, you may have wondered about the title of this piece. “Engineer and master craftsman” is what Newton had carved on his father’s gravestone in Kelbrook Churchyard. I reckon he deserves the same epitaph.

If you’ve stayed the course you now know the bare bones of the history of Henry Brown Sons and Pickles. I think you may have also realised that I have a bad case of hero worship, nowt wrong with that! We still need our heroes. What I want to do now is put some flesh on the bones, I want to look at some of the jobs that they did. I don’t know about you, but I think this tells us more than the bare facts. Let’s go and get our hands dirty and find out what they did for a living.

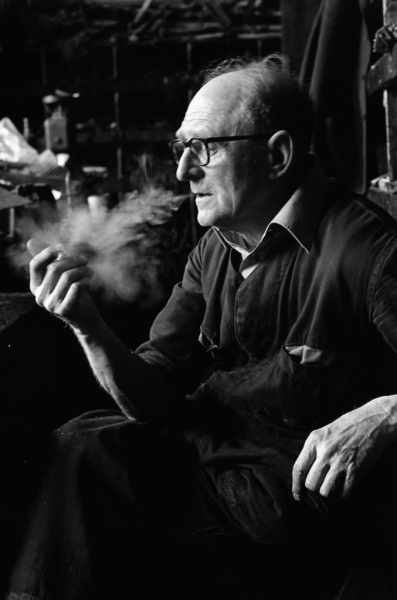

Stanley and Newton playing out at Ellenroad in 1985. We had lots of adventures together after he retired and I think you can see how well we got on with each other. Lovely man.......