PLENTY AND WANT IN WEST CRAVEN PART 4

Posted: 03 May 2013, 07:43

PLENTY AND WANT 04

In a good season, the settled life of the small farmers was more assured but there was always the risk of a famine year. These could be the result of bad weather or even sometimes clouds of dust and ash obscuring the sun after massive volcanic eruptions. Remember that all produce was local and once stocks were used up starvation loomed. At times like this there was only one thing to do, revert to hunter-gathering and go out to scour the local countryside for anything that could be eaten. This is a very deep-rooted instinct and explains why there were so many prosecutions for poaching in depression years in Barlick. Ernie Roberts told me how, in the 1930s, when the family was destitute they used to trap starlings and roast them whole on the fire. His brother had an old muzzle-loading gun and Ernie told me that on one day when they had a charge of powder but no shot, his brother stole the ball-bearings out of a cycle front wheel and used them instead. He came back with a rabbit, as Ernie said, he was a good provider. As Ernie shows, real poverty and want was with us and persists to the present day. However, as transport improved, famine years became a thing of the past. If the crops failed in one locality there was access to other more fortunate areas.

From the earliest Saxon times, not long after the Romans left in about 450AD, villages were getting organised. The old tribal structure had given way to the system of Manors where one man controlled an area. I think that we can assume that this privilege also carried the duty of charity to those who were in need. We don't know how efficient this was, there are no records. As Christianity took hold Ecclesiastical law became more important and with the establishment of parishes the first centre of local administration, below the Manorial Court, was the Vestry. Literally a meeting of town elders in the vestry of the church. This resulted in a system of Parish Relief, often in conjunction with a local monastic order, it was financed by a 'Poor Rate', an imposition or tax on those who could afford to pay and this system was still in place during the early 20th century. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the mid 16th century the system of alms given by the monks to the poor collapsed and it soon became obvious that something had to be done. Apart from anything else, sturdy hungry peasants were a hotbed for rebellion and had to be controlled. This led, under Elizabeth I to the 'New Poor Law' which established by statute that relief would be given to 'worthy' applicants but that the level given should not be better than a person in work. The doctrine of 'Lesser Eligibility' had been codified and is still with us today.

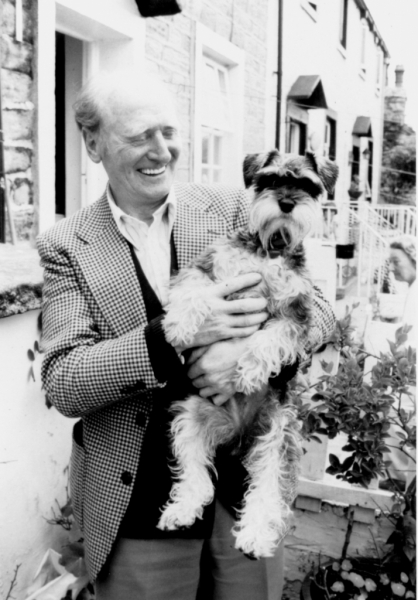

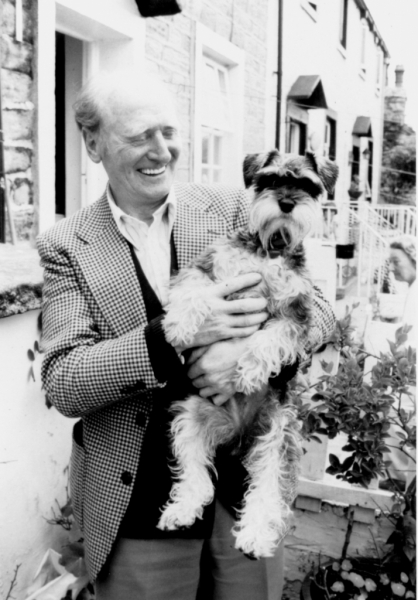

Ernie Roberts in better days, 1983 and he's retired.

In a good season, the settled life of the small farmers was more assured but there was always the risk of a famine year. These could be the result of bad weather or even sometimes clouds of dust and ash obscuring the sun after massive volcanic eruptions. Remember that all produce was local and once stocks were used up starvation loomed. At times like this there was only one thing to do, revert to hunter-gathering and go out to scour the local countryside for anything that could be eaten. This is a very deep-rooted instinct and explains why there were so many prosecutions for poaching in depression years in Barlick. Ernie Roberts told me how, in the 1930s, when the family was destitute they used to trap starlings and roast them whole on the fire. His brother had an old muzzle-loading gun and Ernie told me that on one day when they had a charge of powder but no shot, his brother stole the ball-bearings out of a cycle front wheel and used them instead. He came back with a rabbit, as Ernie said, he was a good provider. As Ernie shows, real poverty and want was with us and persists to the present day. However, as transport improved, famine years became a thing of the past. If the crops failed in one locality there was access to other more fortunate areas.

From the earliest Saxon times, not long after the Romans left in about 450AD, villages were getting organised. The old tribal structure had given way to the system of Manors where one man controlled an area. I think that we can assume that this privilege also carried the duty of charity to those who were in need. We don't know how efficient this was, there are no records. As Christianity took hold Ecclesiastical law became more important and with the establishment of parishes the first centre of local administration, below the Manorial Court, was the Vestry. Literally a meeting of town elders in the vestry of the church. This resulted in a system of Parish Relief, often in conjunction with a local monastic order, it was financed by a 'Poor Rate', an imposition or tax on those who could afford to pay and this system was still in place during the early 20th century. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the mid 16th century the system of alms given by the monks to the poor collapsed and it soon became obvious that something had to be done. Apart from anything else, sturdy hungry peasants were a hotbed for rebellion and had to be controlled. This led, under Elizabeth I to the 'New Poor Law' which established by statute that relief would be given to 'worthy' applicants but that the level given should not be better than a person in work. The doctrine of 'Lesser Eligibility' had been codified and is still with us today.

Ernie Roberts in better days, 1983 and he's retired.