THE PUBLIC CLOCK

Posted: 21 Jun 2013, 07:57

THE PUBLIC CLOCK

When the ringing of bells to mark the liturgy of the hours was banned in England as part of the Reformation the public lost a useful measure of time and domestic clocks, though they existed, were only for the very rich. There was, in modern terms, a gap in the market. Until quite recently it was thought that clocks like those at Salisbury Cathedral and Wells were installed in the 14th century but doubt has been cast on this and now it is thought that the earliest true clocks that controlled either the striking of bells on the hour or clock faces on church towers are more likely to date from the 16th century, coinciding with the ban on bell-ringing. The main reason for them was to signal the times of church services but as they became more common they were increasingly seen as public time-measuring devices. Bear in mind that there was no standard time and so no two clocks agreed with each other.

In 1839 the Great Western Railway installed the first comprehensive electric telegraph system and one of its uses was to give accurate time checks to stations along the line. This was essential as local time varied from station to station and this meant that trains could not be accurately scheduled. The Telegraph Act of 1869 gave the General Post Office a monopoly of services replacing the private companies that were springing up and once again, in addition to messages, an accurate time signal based on Greenwich Observatory could be sent to all post offices which had a public clock and this became a convenient and accurate time check for the man in the street. There was only one problem, the two services were not synchronised and we know from the minute books of the Calf Hall Shed Company in December 1895 that they had a problem because the post office clock used by the workers was running behind the railway clock which was used by the Manchester Man to set his watch and who then passed the 'correct' time on to the engineer, Mr Sneath. The consequence was that officially all the workers were late each morning. Mr Sneath was instructed to use post office time.

The thing that amuses me about this is that it demonstrates how important time-keeping was, “punctuality was the politeness of princes and the courtesy of kings”. These days we all have access to quartz timepieces that would have taken up two rooms in Manchester University in 1950 but punctuality seems to have slipped down the order of precedence. This is probably me betraying my age but the world ran much better in the days when all the weavers were at their looms when I started the engine at Bancroft Mill. In the days before WW2 when tramp weavers stood in the warehouse ready to take the looms off anyone who was late, time-keeping was a serious matter and this habit survived as long as the mills.

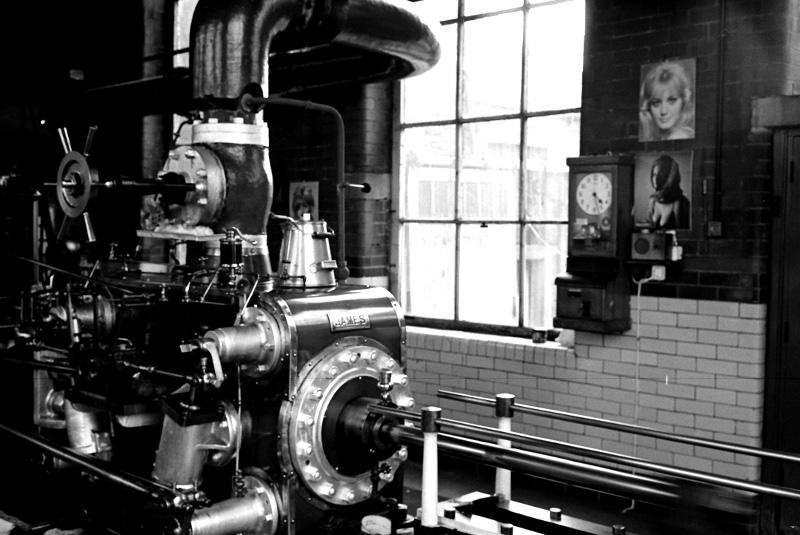

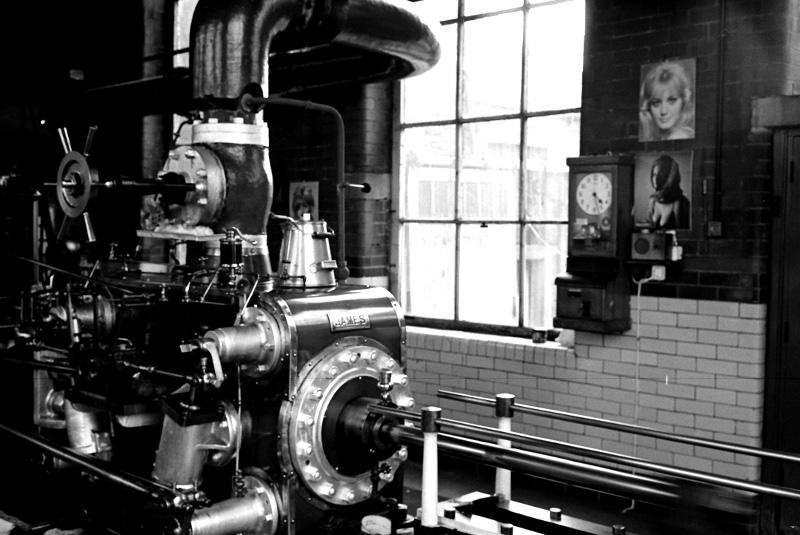

The engine house clock at Bancroft Shed

When the ringing of bells to mark the liturgy of the hours was banned in England as part of the Reformation the public lost a useful measure of time and domestic clocks, though they existed, were only for the very rich. There was, in modern terms, a gap in the market. Until quite recently it was thought that clocks like those at Salisbury Cathedral and Wells were installed in the 14th century but doubt has been cast on this and now it is thought that the earliest true clocks that controlled either the striking of bells on the hour or clock faces on church towers are more likely to date from the 16th century, coinciding with the ban on bell-ringing. The main reason for them was to signal the times of church services but as they became more common they were increasingly seen as public time-measuring devices. Bear in mind that there was no standard time and so no two clocks agreed with each other.

In 1839 the Great Western Railway installed the first comprehensive electric telegraph system and one of its uses was to give accurate time checks to stations along the line. This was essential as local time varied from station to station and this meant that trains could not be accurately scheduled. The Telegraph Act of 1869 gave the General Post Office a monopoly of services replacing the private companies that were springing up and once again, in addition to messages, an accurate time signal based on Greenwich Observatory could be sent to all post offices which had a public clock and this became a convenient and accurate time check for the man in the street. There was only one problem, the two services were not synchronised and we know from the minute books of the Calf Hall Shed Company in December 1895 that they had a problem because the post office clock used by the workers was running behind the railway clock which was used by the Manchester Man to set his watch and who then passed the 'correct' time on to the engineer, Mr Sneath. The consequence was that officially all the workers were late each morning. Mr Sneath was instructed to use post office time.

The thing that amuses me about this is that it demonstrates how important time-keeping was, “punctuality was the politeness of princes and the courtesy of kings”. These days we all have access to quartz timepieces that would have taken up two rooms in Manchester University in 1950 but punctuality seems to have slipped down the order of precedence. This is probably me betraying my age but the world ran much better in the days when all the weavers were at their looms when I started the engine at Bancroft Mill. In the days before WW2 when tramp weavers stood in the warehouse ready to take the looms off anyone who was late, time-keeping was a serious matter and this habit survived as long as the mills.

The engine house clock at Bancroft Shed