BARLICK LIFE 1900 ONWARDS.

Posted: 10 May 2024, 03:35

(Ican't find these articles on the site and suspect they were never posted. This will rectify the omission.

BARLICK LIFE 1900 ONWARDS. (1)

I’m going to try to give you an impression of what life was like early in the 20th century in Barlick, to be more specific, in the Westgate and Colne Road part of the town. The reason I’m concentrating on this area is that my descriptions are based on the life of a friend of mine, Ernie Roberts, who used to be a tackler at Bancroft Shed. Twenty three years ago I sat down with Ernie and got him to tell me his life story so all the circumstances and incidents I shall describe are just as Ernie related them to me. This doesn’t mean that every tiny detail will be correct, memory plays tricks on all of us, however, what you can be sure of is that the overall picture is accurate. So the next time the kids are whingeing because they haven’t got the latest piece of software for their computer or the ‘in’ designer label clothes, sit them down and tell them some of this story and see if you can make them believe it!

Margaret Ellen Alton was born in Brierfield in 1895. We don’t know a lot about her early years but by about 1908 she was living in Barlick and working as a weaver at Long Ing Shed. There she met a man called George Ireson Roberts who was also a newcomer to the town. His father was originally a joiner on the Gisburn Estate but shortly after 1900 he was living in Bracewell with his wife who was the village midwife. George was born in 1889 and so was six years older than Margaret. We suspect that when his family moved to Bracewell, he got a job at Long Ing and this might have been one of the reasons for the family making the move from Gisburn, they could get their children into work and have an income from them. Ernie tells later of having an uncle Ernest who lived in Barlick and I think he was George’s brother.

The first thing to realise about this period is that there was a lot of migration into Barlick from the surrounding towns and villages. The magnet that attracted Margaret and George, together with hundreds of others was the fact that the mills were expanding and there was work in the town. The collapse of the Bracewell interests in 1885 had eventually spawned the shed companies and the profits made by the manufacturers in these sheds fuelled a further burst of building in the early part of the twentieth century which culminated in the completion of Bancroft Shed on Saturday 13th of March 1920. The growth was amazing, one simple statistic tells it all, round about 1890 there were 3,000 looms in the town, by 1920 there were 20,000. In 1900, if you had stood below Forrester’s Buildings and looked North you would have seen nothing but fields and the occasional cottage and farmhouse. By 1920 it was a sea of new houses.

On the face of it, the future looked bright for Margaret and George when they got married. We aren’t sure of the date but Ernie said his mother was ‘very young’ and I suspect she could have been married, or at least, bearing children, as early as 1910. The reason I say this is because we know she conceived 10 times before 1916 and once again in 1920. Out of the 11 confinements, four children survived. Two of these confinements were within ten months and both these children died within a fortnight of each other of German Measles at one year old and three months respectively. She ended up in 1920 with three sons and a daughter, all under working age.

Just think about the life Margaret must have had for a moment. By the time she was 25 she had endured ten years of childbearing. As Ernie said, his mother once told him that she could remember walking down the road carrying one baby, leading another by the hand and carrying a third in her belly. This was by no means uncommon in those days. The only method of birth control available to the lower classes was abstinence and it seems fairly obvious that this was fairly thin on the ground.

Having said this, we shouldn’t run away with the idea that Margaret felt hard done to. After all, this was her experience, as far as she knew, all women had this sort of a life. She was probably grateful that she had a man, they had a rented house and there was plenty of work. Unfortunately, this was all to change and things were going to get much worse. In 1914 war broke out with Germany and by 1916 George was called up into the army, Margaret was left on her own tending her three children. Almost at the end of the war, George was very badly wounded. He survived and came home a broken man, never to work again.

George may have been badly disabled but he fathered another child, Wilson Roberts who was born in 1920, a year before his father eventually died. By this time they had moved into a smaller and cheaper house, number one, John Street. This was a one up and one down house and all six of them lived in one room downstairs and one bedroom with two beds. This is where our story about life in Wapping really starts because this is the house Ernie remembers from his childhood.

John Street was owned by a man called Lund. Ernie’s mother used to call him ‘Monkey’ Lund. Legend had it that he’d bought the entire row of houses for £300 and he lived in one and rented the others out. Ernie said that they got notice to quit every week, not because his mother didn’t pay the rent, but because the two lads, Fred the eldest, and Ernie his brother were so mischievous.

The first thing I got Ernie to do was describe the house in detail. The downstairs room, the parlour as they called it, was stone-flagged and there were no carpets. There was a sink and a gas stove rented off the Council. The reason why it was from the Council is that in those days the Urban District Council ran the gas undertaking having bought it in 1892 from the old Barnoldswick Gas and Light Company. It was a big, cast iron stove, black leaded and Ernie says it took any amount of punishment. It cost 5/- a year to rent. [25p.]

The sink was a stone slopstone. Theses were about three feet long, two feet wide and about four inches deep with a brass plughole and plug. There was a cold water tap but that was all, no hot water and this was the only tap in the house. I’ve lived with a stone sink and the thing I always remember is that no matter how well you cleaned them, they always had a smell about them. I suppose it was because the stone was porous and grease soaked into them.

They had gas lighting downstairs, one jet with a mantle. Ernie said that you always had to keep the door closed in summer when the gas was on because otherwise it attracted moths and these headed straight for the light and broke the mantle. If you were hard up, this was a serious matter.

The only furniture in the room was a square table, a dresser, two chairs and a horse hair sofa. There was one other prized item, an oak corner cupboard which Ernie said was his mother’s pride and joy, he reckoned it was the one piece she had started her marriage with. There was a story attached to this cupboard. At one time, in the early days, when both she and her husband were working, they had saved six half sovereigns and they were hidden in this corner cupboard. They went out one evening and when they came back they had been burgled and the six half sovereigns had gone. Can you imagine what a loss that was? It was the equivalent of a months wages nowadays and Ernie said his mother never got over it.

The seating arrangements at mealtimes were a bit of a lottery. Only two people could sit, when his father was alive it was father and mother. After 1921 when his father died it was first come first served for the other chair. Latecomers stood at the table to eat.

The floor was covered with a sprinkling of sand. This was the usual way to maintain a stone floor. Once a week it was swept and scrubbed and sand scattered on it. During the week the constant walking on the sand scoured the floor and kept the flags clean. The sand wasn’t sand as we know it which is all water worn and has rounded edges on the individual grains, what they used for the floors was finely crushed sand stone which tended to bite into the flags and stay where it was scattered. There were no curtains as we would know them. What people used was a piece of mill cotton, what was known as a ‘skive’ usually, that is a faulty length which had been cut out of a piece. This was died with either a ‘Dolly Blue’ or a ‘Dolly Yellow’ to give them a tint. If you don’t know what these are, ask your mother or grandma, they’ll tell you about them.

I remember asking Ernie if there was any stair carpet and he wanted to know if I was joking! He said that apart from the fact that they couldn’t afford a carpet, you can’t nail carpets to stone steps. The bedroom furniture was simple, a chest of drawers and two beds, end of story.

Some of the young ones might be asking at this point, what about the bathroom and lavatory. Simple, there wasn’t any. There was a tin bath hung on the wall outside and every Friday night it was brought in, placed in front of the fire and enough kettles boiled to give six inches of warm water if you were lucky. Everyone took turns in the same water and when you’d finished with six of you it was getting fairly thick. To empty it you dipped the water out with a lading tin like a big scoop and filled buckets and emptied them outside in the gully. When the bath was light enough you dragged it out, tipped the water out and hung it on the wall again ready for next week. If next door was harder up than you they might borrow your bath. It wasn’t unusual to see a bath walking about the back streets on a Friday night up-ended over someone’s head!

The lavatory was at the end of the row and wasn’t a water closet as we know it. It was simply a wooden board with a hole in it over a tin bucket. You used torn-up newspaper for toilet paper and once a week the Council sent a cart round and the bucket was emptied into it, scattered with disinfectant powder and replaced. More about the ‘night soil’ men later.

That’s all we have room for this week, I’ll come back to the domestic arrangements at 1 John Street next week. Thanks for all the feedback, Stanley@barnoldswick.freeserve.co.uk or 813527 will get me any time if you have any comments or requests.

SCG/27 May 2001

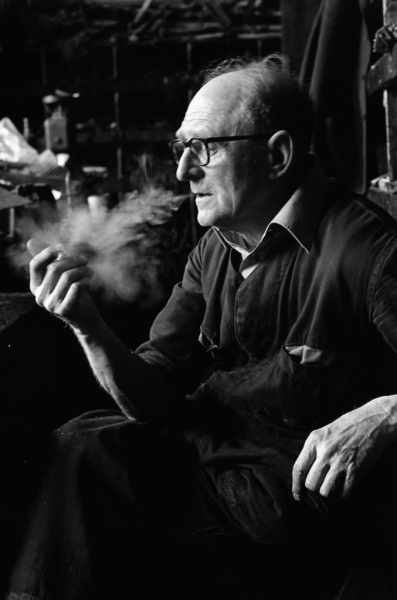

1 John Street in 1979.

BARLICK LIFE 1900 ONWARDS. (1)

I’m going to try to give you an impression of what life was like early in the 20th century in Barlick, to be more specific, in the Westgate and Colne Road part of the town. The reason I’m concentrating on this area is that my descriptions are based on the life of a friend of mine, Ernie Roberts, who used to be a tackler at Bancroft Shed. Twenty three years ago I sat down with Ernie and got him to tell me his life story so all the circumstances and incidents I shall describe are just as Ernie related them to me. This doesn’t mean that every tiny detail will be correct, memory plays tricks on all of us, however, what you can be sure of is that the overall picture is accurate. So the next time the kids are whingeing because they haven’t got the latest piece of software for their computer or the ‘in’ designer label clothes, sit them down and tell them some of this story and see if you can make them believe it!

Margaret Ellen Alton was born in Brierfield in 1895. We don’t know a lot about her early years but by about 1908 she was living in Barlick and working as a weaver at Long Ing Shed. There she met a man called George Ireson Roberts who was also a newcomer to the town. His father was originally a joiner on the Gisburn Estate but shortly after 1900 he was living in Bracewell with his wife who was the village midwife. George was born in 1889 and so was six years older than Margaret. We suspect that when his family moved to Bracewell, he got a job at Long Ing and this might have been one of the reasons for the family making the move from Gisburn, they could get their children into work and have an income from them. Ernie tells later of having an uncle Ernest who lived in Barlick and I think he was George’s brother.

The first thing to realise about this period is that there was a lot of migration into Barlick from the surrounding towns and villages. The magnet that attracted Margaret and George, together with hundreds of others was the fact that the mills were expanding and there was work in the town. The collapse of the Bracewell interests in 1885 had eventually spawned the shed companies and the profits made by the manufacturers in these sheds fuelled a further burst of building in the early part of the twentieth century which culminated in the completion of Bancroft Shed on Saturday 13th of March 1920. The growth was amazing, one simple statistic tells it all, round about 1890 there were 3,000 looms in the town, by 1920 there were 20,000. In 1900, if you had stood below Forrester’s Buildings and looked North you would have seen nothing but fields and the occasional cottage and farmhouse. By 1920 it was a sea of new houses.

On the face of it, the future looked bright for Margaret and George when they got married. We aren’t sure of the date but Ernie said his mother was ‘very young’ and I suspect she could have been married, or at least, bearing children, as early as 1910. The reason I say this is because we know she conceived 10 times before 1916 and once again in 1920. Out of the 11 confinements, four children survived. Two of these confinements were within ten months and both these children died within a fortnight of each other of German Measles at one year old and three months respectively. She ended up in 1920 with three sons and a daughter, all under working age.

Just think about the life Margaret must have had for a moment. By the time she was 25 she had endured ten years of childbearing. As Ernie said, his mother once told him that she could remember walking down the road carrying one baby, leading another by the hand and carrying a third in her belly. This was by no means uncommon in those days. The only method of birth control available to the lower classes was abstinence and it seems fairly obvious that this was fairly thin on the ground.

Having said this, we shouldn’t run away with the idea that Margaret felt hard done to. After all, this was her experience, as far as she knew, all women had this sort of a life. She was probably grateful that she had a man, they had a rented house and there was plenty of work. Unfortunately, this was all to change and things were going to get much worse. In 1914 war broke out with Germany and by 1916 George was called up into the army, Margaret was left on her own tending her three children. Almost at the end of the war, George was very badly wounded. He survived and came home a broken man, never to work again.

George may have been badly disabled but he fathered another child, Wilson Roberts who was born in 1920, a year before his father eventually died. By this time they had moved into a smaller and cheaper house, number one, John Street. This was a one up and one down house and all six of them lived in one room downstairs and one bedroom with two beds. This is where our story about life in Wapping really starts because this is the house Ernie remembers from his childhood.

John Street was owned by a man called Lund. Ernie’s mother used to call him ‘Monkey’ Lund. Legend had it that he’d bought the entire row of houses for £300 and he lived in one and rented the others out. Ernie said that they got notice to quit every week, not because his mother didn’t pay the rent, but because the two lads, Fred the eldest, and Ernie his brother were so mischievous.

The first thing I got Ernie to do was describe the house in detail. The downstairs room, the parlour as they called it, was stone-flagged and there were no carpets. There was a sink and a gas stove rented off the Council. The reason why it was from the Council is that in those days the Urban District Council ran the gas undertaking having bought it in 1892 from the old Barnoldswick Gas and Light Company. It was a big, cast iron stove, black leaded and Ernie says it took any amount of punishment. It cost 5/- a year to rent. [25p.]

The sink was a stone slopstone. Theses were about three feet long, two feet wide and about four inches deep with a brass plughole and plug. There was a cold water tap but that was all, no hot water and this was the only tap in the house. I’ve lived with a stone sink and the thing I always remember is that no matter how well you cleaned them, they always had a smell about them. I suppose it was because the stone was porous and grease soaked into them.

They had gas lighting downstairs, one jet with a mantle. Ernie said that you always had to keep the door closed in summer when the gas was on because otherwise it attracted moths and these headed straight for the light and broke the mantle. If you were hard up, this was a serious matter.

The only furniture in the room was a square table, a dresser, two chairs and a horse hair sofa. There was one other prized item, an oak corner cupboard which Ernie said was his mother’s pride and joy, he reckoned it was the one piece she had started her marriage with. There was a story attached to this cupboard. At one time, in the early days, when both she and her husband were working, they had saved six half sovereigns and they were hidden in this corner cupboard. They went out one evening and when they came back they had been burgled and the six half sovereigns had gone. Can you imagine what a loss that was? It was the equivalent of a months wages nowadays and Ernie said his mother never got over it.

The seating arrangements at mealtimes were a bit of a lottery. Only two people could sit, when his father was alive it was father and mother. After 1921 when his father died it was first come first served for the other chair. Latecomers stood at the table to eat.

The floor was covered with a sprinkling of sand. This was the usual way to maintain a stone floor. Once a week it was swept and scrubbed and sand scattered on it. During the week the constant walking on the sand scoured the floor and kept the flags clean. The sand wasn’t sand as we know it which is all water worn and has rounded edges on the individual grains, what they used for the floors was finely crushed sand stone which tended to bite into the flags and stay where it was scattered. There were no curtains as we would know them. What people used was a piece of mill cotton, what was known as a ‘skive’ usually, that is a faulty length which had been cut out of a piece. This was died with either a ‘Dolly Blue’ or a ‘Dolly Yellow’ to give them a tint. If you don’t know what these are, ask your mother or grandma, they’ll tell you about them.

I remember asking Ernie if there was any stair carpet and he wanted to know if I was joking! He said that apart from the fact that they couldn’t afford a carpet, you can’t nail carpets to stone steps. The bedroom furniture was simple, a chest of drawers and two beds, end of story.

Some of the young ones might be asking at this point, what about the bathroom and lavatory. Simple, there wasn’t any. There was a tin bath hung on the wall outside and every Friday night it was brought in, placed in front of the fire and enough kettles boiled to give six inches of warm water if you were lucky. Everyone took turns in the same water and when you’d finished with six of you it was getting fairly thick. To empty it you dipped the water out with a lading tin like a big scoop and filled buckets and emptied them outside in the gully. When the bath was light enough you dragged it out, tipped the water out and hung it on the wall again ready for next week. If next door was harder up than you they might borrow your bath. It wasn’t unusual to see a bath walking about the back streets on a Friday night up-ended over someone’s head!

The lavatory was at the end of the row and wasn’t a water closet as we know it. It was simply a wooden board with a hole in it over a tin bucket. You used torn-up newspaper for toilet paper and once a week the Council sent a cart round and the bucket was emptied into it, scattered with disinfectant powder and replaced. More about the ‘night soil’ men later.

That’s all we have room for this week, I’ll come back to the domestic arrangements at 1 John Street next week. Thanks for all the feedback, Stanley@barnoldswick.freeserve.co.uk or 813527 will get me any time if you have any comments or requests.

SCG/27 May 2001

1 John Street in 1979.