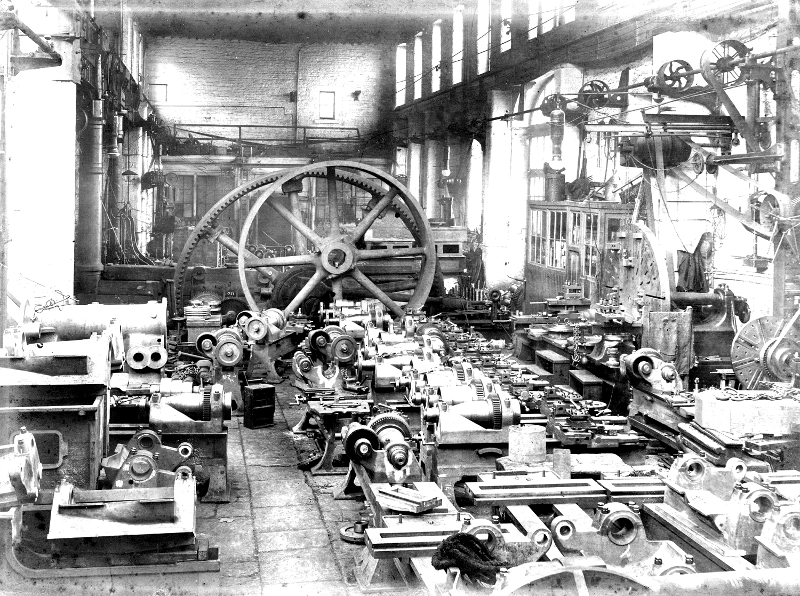

By early 1915 shortages of ammunition and equipment for the troops on the Western Front became a pressing matter. The first and most famous deficiency was the 'Shell Crisis' caused by the change of strategy which called for heavy artillery bombardment of enemy lines to soften them up before an attack. This new scale of warfare hadn't been foreseen by the military planners and in May 1915 it resulted in Asquith sacking all his ministers, forming a coalition government and appointing Lloyd George to a new post, Minister of Munitions. One of his first tasks was to coerce the engineering industry into making more shells. Special lathes were needed for shell manufacture and amongst many others, Burnley Ironworks turned over all their production to making shell lathes.

In Barlick, Henry Brown and Sons got an enquiry from Yates and Thom at Blackburn who wanted some large gun bases turning for the war effort. They were full up with work and needed a sub-contractor. Browns hadn’t a lathe big enough to do the job and there wasn’t one available to buy because of war restrictions but Johnny Pickles, their foreman, said this was no problem, they could make one. He sat down in the kitchen at home and designed the lathe. The patterns were made at Wellhouse shop and the castings at Ouzledale and Stanley Fisher (Walt Fisher’s father and eventually the last engineer at Moss Shed in Barlick) and Johnny built the lathe in Wellhouse works. It was a big useful machine, a ‘break lathe’. It had a 48 inch face plate, could take 36 inches over the saddle and was eighteen feet between centres. I have seen Newton working on this lathe truing the driving wheels from a Stanier ‘Black Five’ locomotive and these were six feet diameter. You needed big tools for these repairs and this lathe was working right up to the firm finishing in 1981. In WW2 it was used for making bases for anti-aircraft guns.

The mills in Barlick were affected as well but in a different way. The main explosive used as a propellant in ammunition was cordite or 'gun-cotton' It was made by a chemical reaction on raw cotton which was mainly cellulose. This meant that a large part of the cotton imported was diverted away from textiles and into the war effort and there was some short-time working in the local weaving sheds. Coal production became a problem until the government made mining a reserved occupation and brought many miners who had volunteered for the army back into the industry. Coal became scarce and prices rose so this affected the weaving sheds as well. The government took over the allocation of all food and raw materials and what we now call a 'war economy' was put in place. This turned out to be a good practice run for the Second World War as the same system was brought in straight away. It wasn't just military strategy that had to be changed.

Shell lathes at Burnley Ironworks in 1917.