You’ll have to forgive me if I go on a bit here but I am going to deal with one of the high points of my career as an engineer. What I was proposing to do was to run the biggest textile mill engine in the world for the first time since 1974 with no insurance and several serious faults in the system. I didn’t do it lightly, I knew the risks but I also recognised that nothing would enthuse Coates more than seeing the engine in steam. Besides, I had the biggest Meccano set in the world to play with and I wasn’t going to pass this chance up!

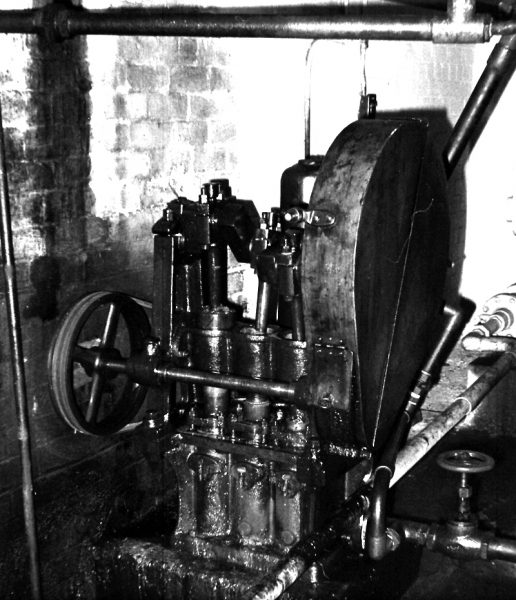

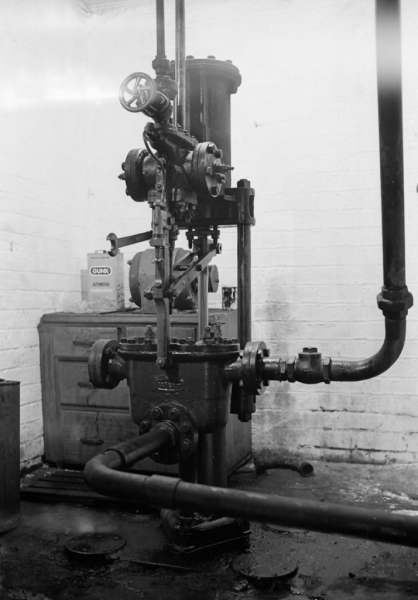

I had an engine connected to a boiler and about ten tons of coal in the bunker. What I didn’t have was a feed pump that would work against pressure because of a frost damaged main. I also had no electricity supply. I started by giving the engine a thorough oiling and injecting a mixture of diesel and oil into all the cylinders to soak into the rust and the rings. I kept on doing this for a week until I was sure I had got as much lubrication into the bores and moving parts as I could. Then I took the lid off the boiler and put about 3,000 gallons of water in with a fire hose. When I had it full to the top I put the lid back on and fired up. As soon as I had steam I got the big Weir steam pump in the pump house going and tested the feed line. As I suspected it was cracked by frost and this meant we couldn’t put any water in while there was pressure on the boiler. I went home that night leaving a crack of steam going into the engine to warm it through. I had already warned Newton Pickles and the next day in February 1985 he and I went to Ellenroad and had a real play out!

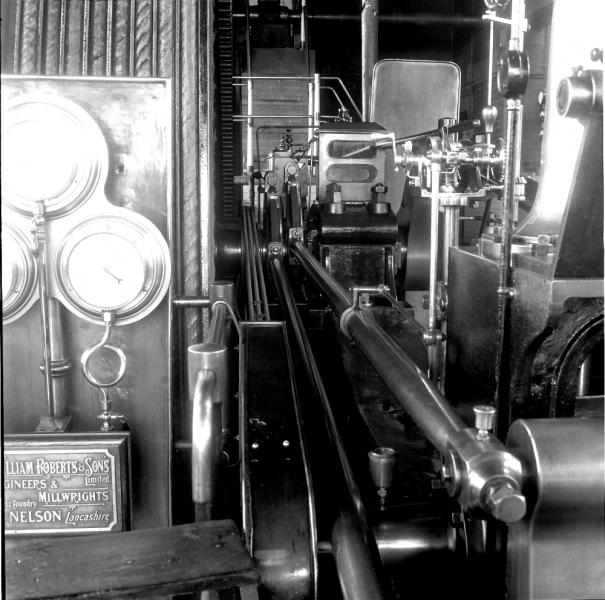

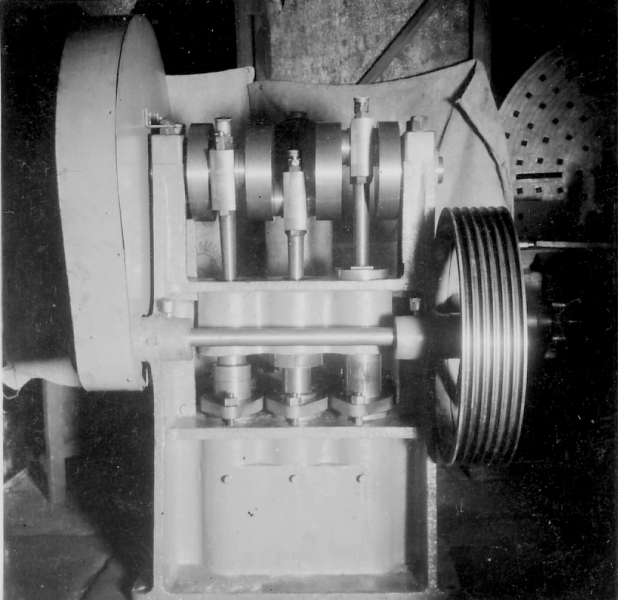

While Newton did last minute oiling, essential because we had hardly any lubricators on the engine and would need all the initial lubrication we could get, I fired the boiler until we had 140psi on the clock. I should say at this point that there was an additional problem with the engine as in its last year of running, the right hand connecting rod had been removed and the engine was run on the left hand side only. We had no knowledge of how well the connecting rod had been re-installed. The parts of the engine are so large that you couldn’t just go and shake a bearing to see how much play there was in it, I had inspected it and as far as I could see it was safe enough to run. We would know more about it when we got it moving.

We had reached the point where we had to go for it. We couldn’t put any more water in the boiler and so had to gauge the fires against the water level. We locked the engine house door, Newton took station next to the valve gear and held the steam valve on the cylinder wide open and I opened the 18” stop valve. Nothing happened. There were surprisingly few leaks but even so, the engine house started to fill with steam. My heart was dropping into my boots when there was a grunt from the engine and Newton shouted “It’s away, the seal has broken!” He meant the grip of the rusty piston rings on the cylinder bores had been overcome by the pressure. By this time I couldn’t see anything at all because of the steam, I was blind and running on sound alone. I heard a groaning noise as the pistons scraped their way through ten tears accumulated muck and rust in the bores on the first stroke and then there was a tremendous shudder ran through the air. “What the hell was that?” I shouted, I was really worried. “Thar’t all reight, it was only the pigeon shit falling off the top of the flywheel!” shouted Newton. There was some thumping from the bearings but the engine started to gather speed, I cut back on the steam in case the governor didn’t get hold but it was OK. As we got up to about 50 rpm the governor took hold and the engine settled down to a noisy but relatively steady running speed. The only draw back, but this was temporary, was the foul smell from the cellar as the four air pumps delivered thousands of gallons of stagnant water into the drain back to the river.

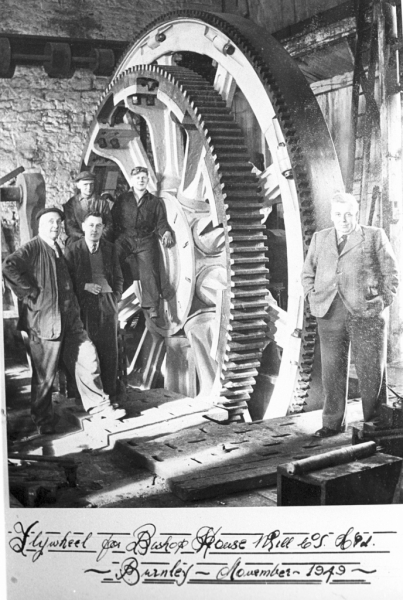

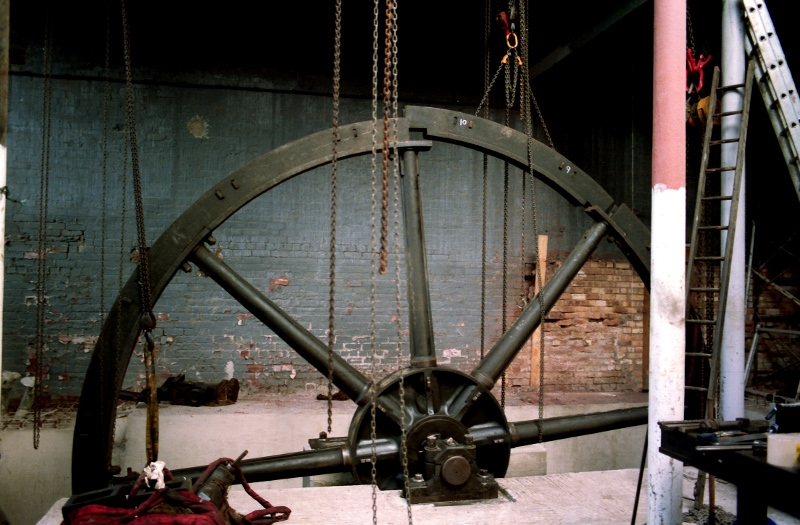

As the seals established themselves the fog started to clear and we saw a glorious sight, the Ellenroad Engine in full flow for the first time in ten years! It was a wonderful moment but we didn’t have a lot of time to appreciate it because we had to start running round pouring oil into the bearings. It was a wonderful quarter of an hour, the engine was badly out of adjustment both in terms of the valves and the bearings but was running and as far as we could see there was nothing fundamentally wrong with it. We decided we had pushed our luck far enough and Newton went to shut the steam off. I told him I wanted to do an experiment as he shut down, I wanted to block the governor open and see how much effect the vacuum had after the steam was turned off. I jammed a brush head under the governor rod and Newton shut the valve down. The engine didn’t slow, it started to speed up and the brush head was stuck fast under the rod. It was getting really serious before it eventually began to slow down. Newton and I agreed afterwards that it must have been doing near enough a hundred revs a minute, far faster than it had ever run in its life before. This was very dangerous as the main danger with these engines is that overspeed increases the tension in the castings of the flywheel so much that they break and the wheel explodes. We got away with it but I made a mental note to do something about it.

This all sounds dangerous, and you’re right, it was. What has to be recognised is that we were in unknown territory here. Nobody had ever run the Ellenroad Engine at full speed with no load, not even ropes on the wheel. Even with the low pressure we were using we were dealing with tremendous forces and we had to know how the engine would react, especially if someone made a mistake. Neither Newton or I ever imagined that there was enough vacuum in the condensers to make it pick its feet up like it did, it surprised even us, but we had to find out and what I did was the only way to do it. I remember reading a memoir by a very famous American engineer and builder of steam engines in the 19th. century, Charles T Porter. In it he said that the faster you run an engine the less movement there is in any loose bearings. He demonstrated this by deliberately slackening bearings off and running his engines at high speed to demonstrate how quietly and well the bearings ran. I never quite believed this until we ran Ellenroad that day at 100rpm. I can assure you it ran like silk even though there was a quarter of an inch of play in the right hand cross head and crank brass! Porter knew his stuff but how else would we have found out?

Eventually, 300 tons of iron came to a stand still and we brewed up, had a pipe and did the inquest. The first thing I asked Newton was why he didn’t run when it overspeeded. “I was waiting on thee!” he said. Now that really is slit trench material! We both agreed that it had run a bloody sight better at 100rpm than 50 because the bearings hadn’t time to knock but we weren’t going to try it again! All told we were like a couple of dogs with two tails apiece. We had reason to be because we’d just made history and proved that the Ellenroad Engine, though it might need some TLC, was a runner! Now we knew we had an engine, we agreed to run it again for Coates. I arranged it with Gavin and he and a few others turned up the following week and we ran one more time in semi-public just to whet their appetites. I think that if any encouragement was needed, this steaming did the trick. None of them had seen anything like it before and they were all suitably awe-struck. Newton and I passed among them in nonchalant manner as if this was something we did every day of the week!

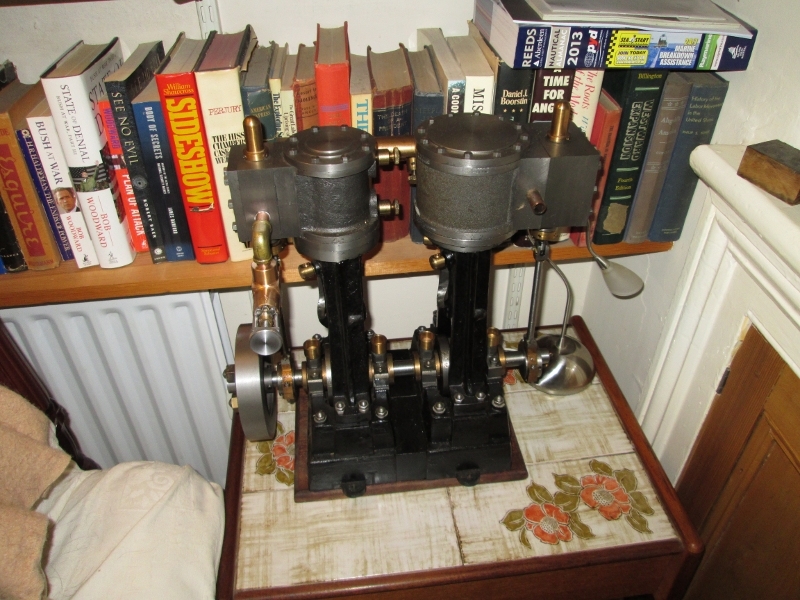

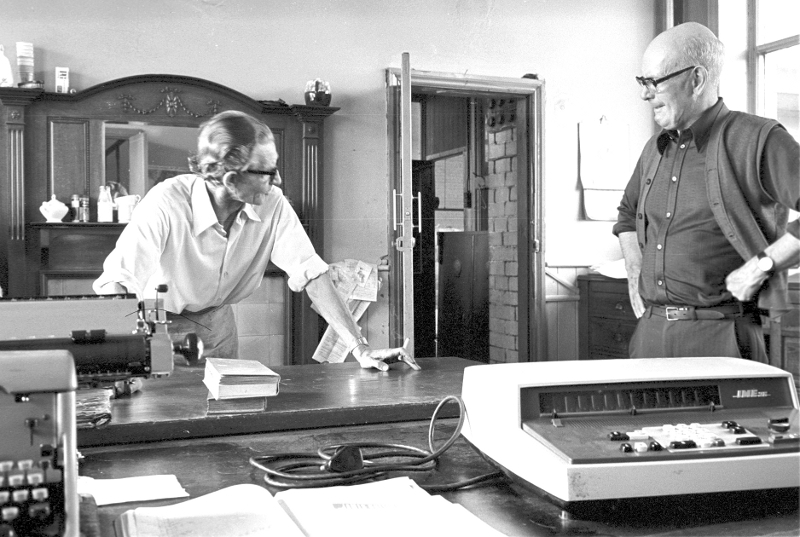

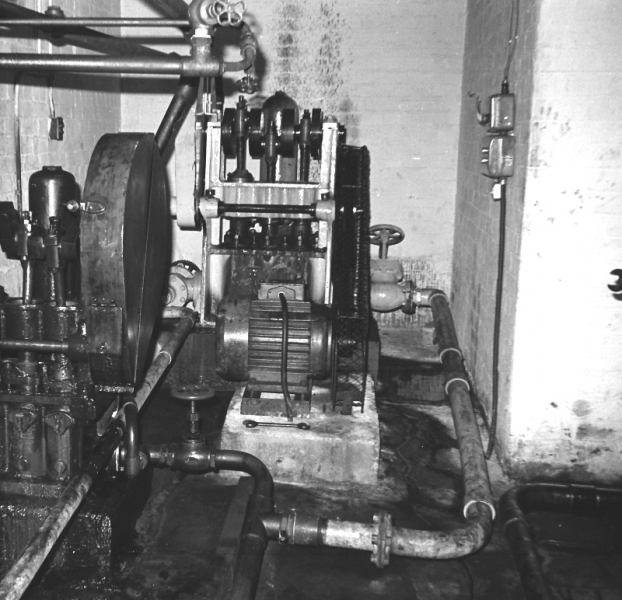

Newton pouring oil direct into the pedestal bearing, the aquarium lubricators had been taken off and stored in a safe location. We were running round like blue arsed flies but I grabbed this shot of my old mate in his element. It was the biggest engine even he had ever run.