Good stokers P as long as you had a good load on.

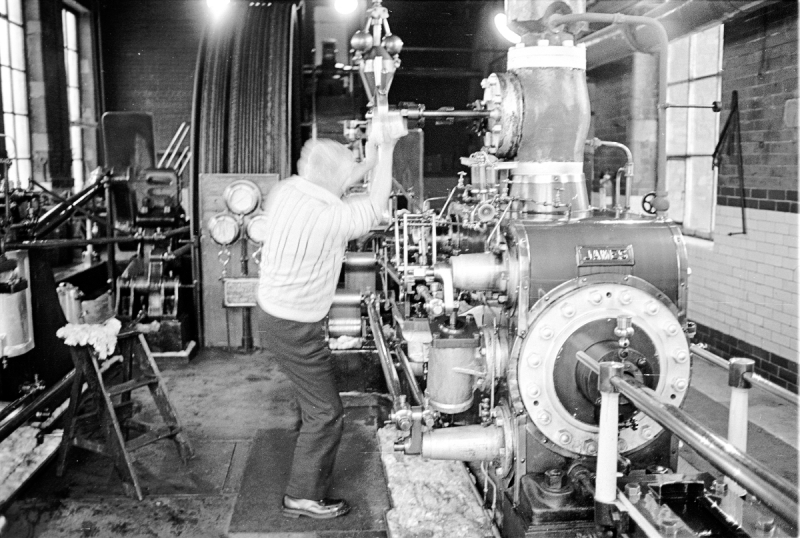

Ben needed a lot of watching for the first few weeks, he wasn’t the liveliest lad in the world and I didn’t really trust him yet. I had my own job in the engine house to attend to and to tell you the truth, could ill afford the time watching my firebeater, it was a stressful time for me. The job of engine tenter carries a lot of responsibility, if you don’t get it right, everybody suffers because they lose pay. On the other hand, if you get it right, the weaving goes better and everybody is happy because the wages go up. On top of all this, starting, controlling and tending for a large machine like a steam engine is a stressful job on its own, when you start it in the morning you are very conscious of the fact that you are handling enough power to kill you if you don’t get it right. It’s not so bad once you get used to it but I can tell you I was fairly hyped up that first week! I soon settled into the collar however and began to get up to mischief!

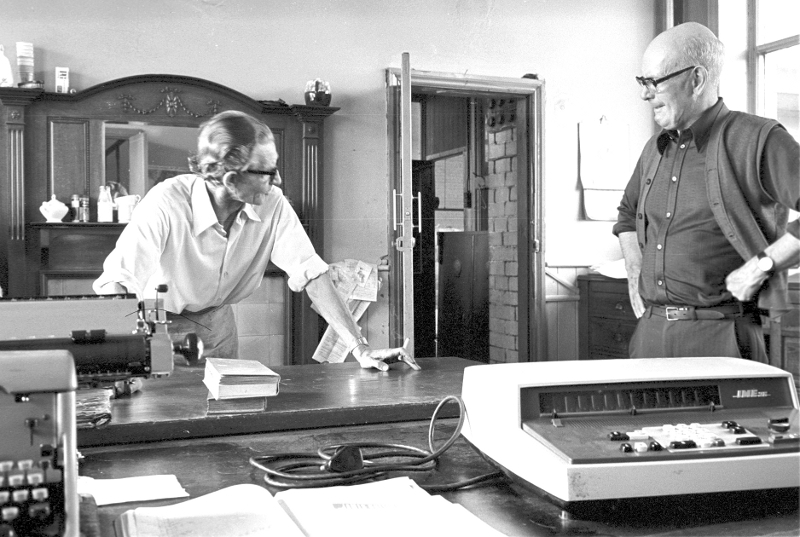

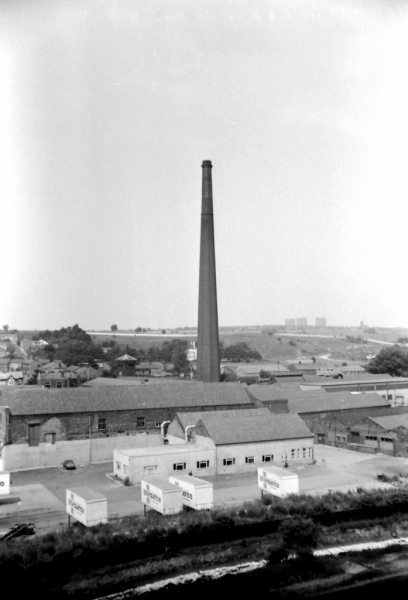

The first thing to realise about Bancroft as a workplace is that it was run on the same lines as any shed like it in the 19th century. The buildings and the machinery were an anachronism, anybody who worked in the first steam driven weaving shed in Barlick in 1827 would have recognised the place and been completely at home. The old hierarchies had been preserved as well, weaving was controlled by the tacklers, Ernie Roberts, Roy Wellock and Ernie Macro in the large cabin and Steve Clark and Albert Gornall in the small one. The winding department was presided over by the winding master, Frank Bleasdale, George’s brother, who had two winders, Judy Northage, and Jean Smith. Warp preparation was divided between Fred Roberts who ran the Barber knotting machine and Jim Pollard who did the drawing in. Tape sizing was done by the tapers, Norman Gray and Joe Nutter. Power and maintenance was the province of the engineer. Overall production was controlled by the weaving manager Jim Pollard. The office was run by Sidney Nutter with part time help on making up days from Eughtred Nutter, his cousin. The mill was owned by K.O. Boardman’s of Stockport and the managing director who came in two or three days a week was Peter Birtles. Incidentally, there was a coincidence here, Peter’s doctor when he was young was Tommy O’Connell same as me, he told me that Tommy was still alive and living in Heaton Moor.

The engine house was always seen as the single most important part of the mill. If the engineer didn’t come in and start on time nobody else could do anything, this wasn’t true of any other job in the mill. The consequence was that the engineer was always left alone, he was a law unto himself and all anybody cared about was whether the engine started to time and ran without trouble. This meant that a lot of people coveted the job and it soon became evident that there were pockets of resentment inside the mill directed against this outsider who had popped up from nowhere and pinched the plum! It sounds a bit petty I know but this was the mechanism that was at work, it took me a while to identify this but I soon worked out where the flack was coming from and dealt with it.

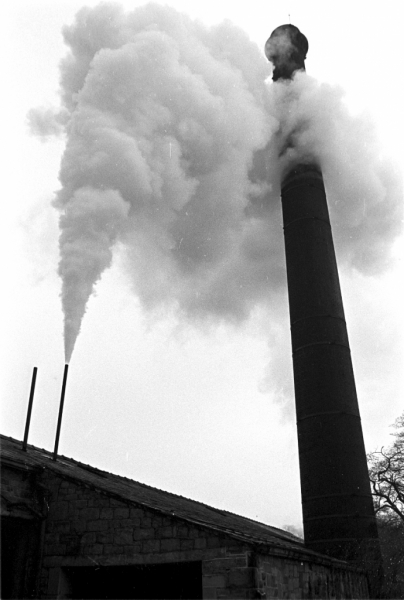

Another factor was that there was a big backlog of maintenance that hadn’t been attended to. Some of it was major stuff like the fact that we hadn’t any reliable way of putting feed water in the boilers. For years George had been making do and we were getting to the stage where a lot of the pigeons were coming home to roost. A lot of these faults were costing money. A good example was the boiler feed, if we could get it right we could save about five tons of coal a week in winter because we could increase the temperature of the feed water to the boiler. I decided not to tackle everything at once but to get settled in.

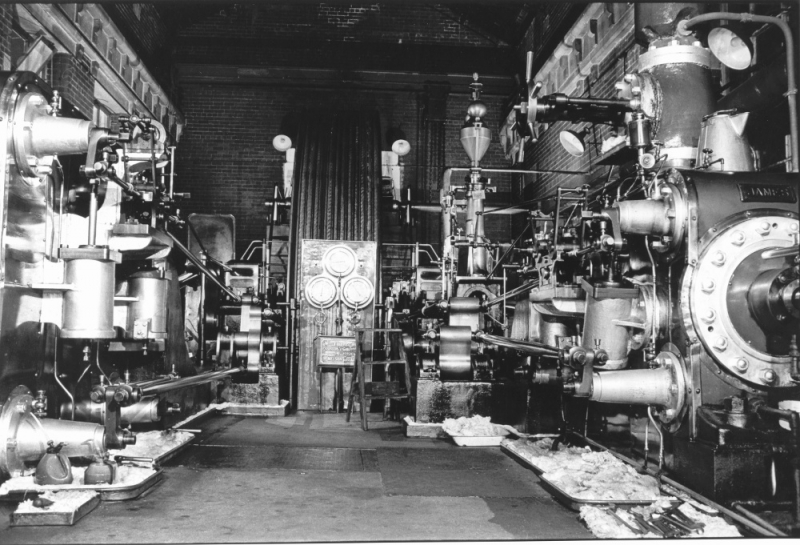

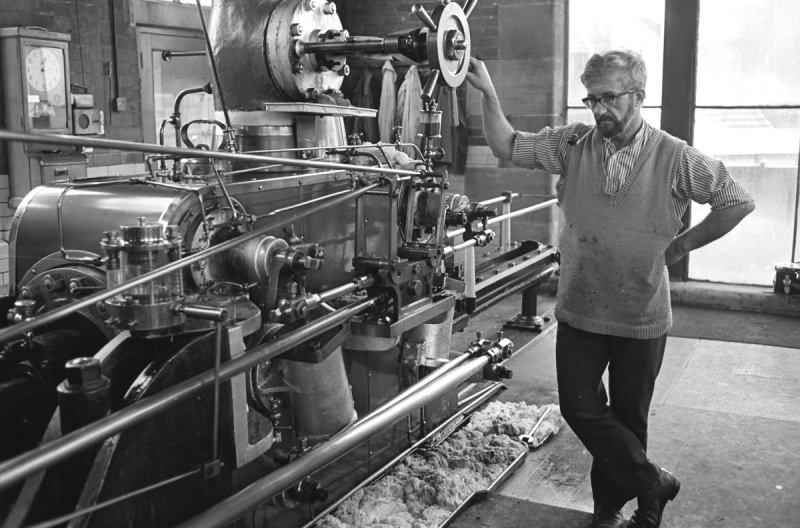

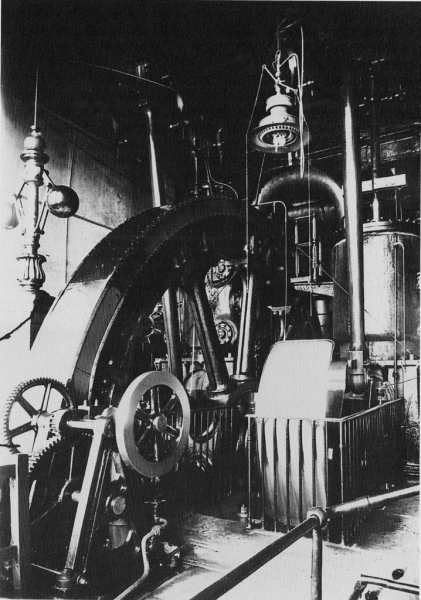

The engine house was about a hundred feet long and fifty feet wide. The walls were glazed brick up to about six feet high and it was warm and well lit. Even nicer, there was a good view of the fields outside so I could run the engine and watch my cattle grazing before I sold the field to Young Sid Demaine. There were carpets down along both sides of the engine, these were to give a good grip on the floor and also tended to trap dust and grit which was a good thing because it was better there than in the bearings. My first job was to move all George’s stuff out of the engine house and put it in the garage. He had a desk, a sofa and all sorts of spare parts for his car. There were also lots of plant pots which he had used for growing tomatoes and flowers in the engine house. All this was chucked out and we had a good clean up, I installed a better desk out of the warehouse and an easy chair in the corner. While the engine was running I couldn’t leave it for more than about five or ten minutes at a time so a bit of comfort was essential.

I relied a lot on Ben Gregory my firebeater. He was learning well and had got to the stage where I could leave him alone to make steam while I got on with my jobs in the engine house, however, we were approaching the heating season and I knew that this would be the testing time for him. A north light shed is about the worst building in the world to heat, the weaving process is very sensitive to humidity, the warps give a lot of trouble if they are too dry so no form of forced heating, such as fans, could be used. We heated the shed by two inch steam pipes at boiler pressure slung about eight feet off the ground and running back and forth across the shed. This meant that any heat put in the shed went straight up into the roof. It was painful to try to get the shed to 55 degrees by starting time. You put steam in the shed and watched the temperature drop for the first two hours as the hot air rose and forced the cold air down! I have seen us have to start steaming the shed at one o’clock in the morning when the weather was really cold so it was going to be essential that Ben was able to get up in the morning. This was a problem waiting to happen so, though it worried me, I had to wait and see.

Jim Pollard the weaving manager and I got on well from the start. I talked with him a lot and he gave me clues as to how things could be improved. The main area I concentrated on in the first instance was to get the engine running as smoothly as possible. The more steadily the engine ran, the better the looms wove and the more pay the weavers earned. It seemed to me that if I could gain an improvement there I would have treasures in heaven and my job in other areas would be a lot easier. I spent hours just sitting there smoking and weighing the engine up. When I was absolutely sure I understood how the engine worked and what the adjustments on the valve gear controlled I started tuning the engine up. Newton took a lot of interest in this, he was really pleased that I actually cared how the place ran and he soon found me an indicator which used to belong to a very good engineer who ran Wellhouse, it cost me £20 but was well worth it. In another place I’ll have a lot to say about how indicators are much over-rated but they have their uses and I started indicating the engine regularly, identifying changes that could be made in the valve events, making the adjustment and then checking again. My final arbiter was always how steadily the engine ran and what reports I got from the weavers.

My main man in the shed was a weaver on the ‘pensioners side’, these were sets of looms containing eight looms each under the lineshaft which were mainly run by people over retiring age, the rest of the sets were ten looms each. He was nicknamed ‘Billy Two Rivers’ (Billy Lambert) and used to be a tackler but had injured his neck and gone back to weaving. He knew his job and I used to go in and have a word with him every morning as to how it was running, I’d take notice of what he said and then go back and make slight adjustments to speed. My adjustments to the valves meant that the engine was running smoother and the final improvement was to give the driving ropes a good dressing. Cotton driving ropes are a wonderful, shock free, flexible drive, if properly looked after they could last forty or fifty years. The main problem was that they wore on the pulleys as they drove.

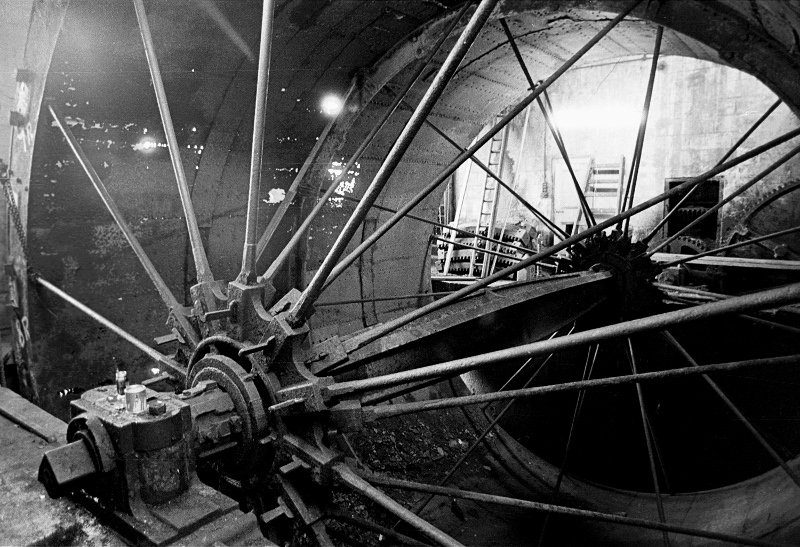

There has always been a controversy about rope drives, some engineers say they drive best and wear longest if the ropes rotate as they drive in the grooves because this evens the wear out. In order to get ropes to do this you have to have the drives slightly out of line to encourage the ropes to roll in the groove. The flywheel and second motion pulley at Bancroft were perfectly aligned and the ropes didn’t roll, this didn’t seem to harm them, some of them were original from when the mill was built in 1919. The best way to give them some protection was to dress them with a mixture of tallow and graphite. I used to set the barring engine on at dinnertime and as it slowly turned the engine I would smear rope grease on the ropes as they passed me until I had given them all a good coat well rubbed in. Funnily enough the grip in the grooves of the flywheel and second motion pulley was improved by lubricating them, I had to slow the engine down slightly when I first greased them. However, after a couple of days running they had polished up and slipped slightly. This made the drive even more smooth and the weavers benefited in the shed. The net result of these adjustments and maintenance was that after about six weeks Jim told me that the average wage in the shed had gone up by £1.50 a week, this on a top wage of £35 so everybody, including the management, was pleased. This was the foundation for the rest of the campaign to get the essential maintenance up to date, the management started to realise it was worth listening to me.

The next target was to get the cellar sorted out and improve our boiler feed arrangements. Ben and I gave the cellar a good clean out and disinfected it. George had been in the habit of peeing down the side of the flywheel into the cellar instead of going out in the cold to the lavatory. The space under the flywheel stank so we scrubbed it out, whitewashed it and shifted all the rubbish. I examined the pumps and came to the conclusion we needed to completely alter the way we fed water to the boiler. This meant a new pump and refurbishment of the old Pearn three throw. I started to hunt round for a pump.

We made our own electricity at Bancroft and in early October as we started to come into the heating season the load on the boiler went up. I started to get complaints from Fred Roberts about there not being enough power to run the Barber knotting machine. This ran on 110 volts DC and any drop in the alternator supply made a big difference to his voltage level. It ran OK off the mains but wouldn’t perform off the engine. His version of it was that I was frightened of the engine and was running it too slow! Not surprisingly this got my back up and I told him that things were no different than they had been for the last twenty years, there was a fault somewhere and I would find it.

I had a fair idea that there was a fault because the electronic adding machine in the office wouldn’t work properly off engine power so I suspected the voltage was down. According to the instruments on the big switch board in the engine house all was OK but I spent £85 on a heavy duty Avometer and did some tests of my own. I found that instead of turning out 450 volts on three phase we were only doing 390, the voltmeter on the board was way out. I tried altering the resistance to the exciter but couldn’t get more than 410 volts so I sent for the sparks and got them to alter the permanent resistances in the circuit. That did the trick! We could get 450 volts now with ease.

Jim came down and told me Fred Roberts was in a right mess. He couldn’t control the knotting machine, it was going too fast. I went up and informed Fred that I had sorted out the problem at my end, he was now on 450 volts as per design and any problems he had were his own, go to it Fred! He never spoke to me again as long as the mill ran, this did not cause me any problems! The calculator in the office was working OK as well.

A side effect of raising the voltage was that the lighting in the shed was much better, this delighted the weavers but gave me a problem because dozens of 150 watt bulbs blew under the higher voltage. I was saved by an earlier stroke of luck. The fair had come to town and I was talking to one of the lads who ran the mobile generators for them and he told me they had a lot of Edison Cap bulbs that were no use to them now. (Screw cap instead of bayonet) He said they were 150 watt, just what we used at the mill so I bought all they had for £15. When we counted them there were a thousand! We didn’t buy another bulb for years. The increased load on the alternator made the belts on the counterdrive slip a bit and I had to attend to that as well. For the first few months it was like this, you put one thing right and it triggered off something else.

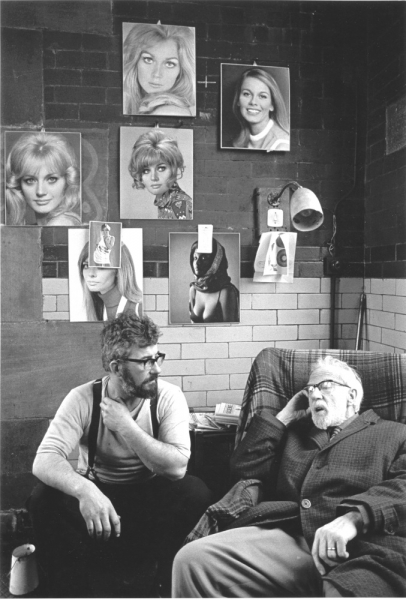

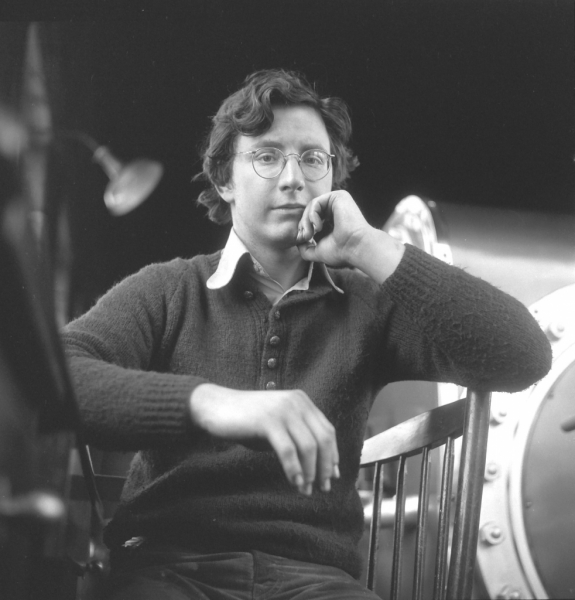

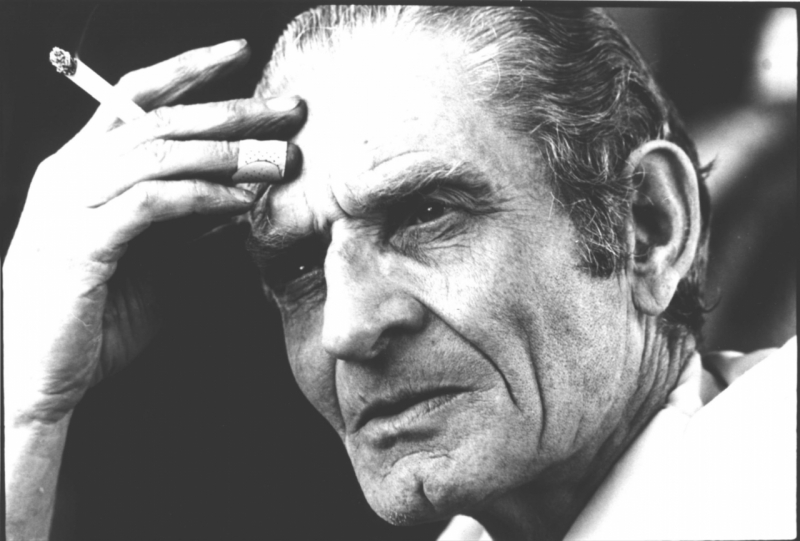

Jim Pollard. A master of his craft and we worked well together.