The next port of call in our search for the history of Henry Brown Sons and Pickles is Kelbrook Main Street where we have to dig into the Pickles family. Kelbrook is a small village about a mile from Earby going towards Colne. The name Pickles comes from Pighkeleys, Pike leys, ‘dweller at the small enclosure’. There are a lot of them! As far as we are concerned at the moment there are three groups in the area, the Pickles of Kelbrook, the Pickles of Barnoldswick who founded the weaving firm of Stephen Pickles and Son of Long Ing and a third group which is all the others we are not sure about. Sorry about that, it’s not good scholarship but we have to know who to discard to get some order into this story!

Our Pickles are the families in Kelbrook who originated in Lothersdale and seem to have migrated over the hill as employment in the mills started to drag labour in from the surrounding districts in the early 19th century. I think I have the ancestry right but as I always remind you, research changes things and I might have to change my mind, however this is the state of play as I write.

We start with George Pickles of 7 Main Street Kelbrook who was a clogger and shoemaker. He must have done fairly well for himself because he was one of the original investors in Sough Bridge Mill when the Kelbrook Mill Company was formed in 1898. He was born in 1828 and according to the 1871 census was in Kelbrook and had a son William who was born in 1857. He seems to have had two more sons, Daniel who returned to Lothersdale and James who became the engineer at Sough Bridge mill just down the road towards Earby. William (1857) had at least two sons, John Albert Pickles, born in Kelbrook in 1885 and Newton who eventually took over the clogger’s shop. John Albert (always known as Johnny) is the one that we have been looking for.

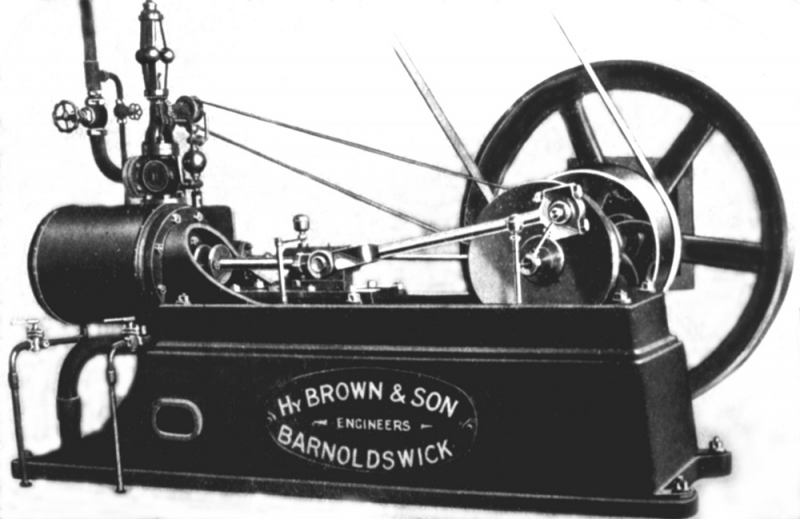

Johnny Pickles was a bright lad who did well at school and when he left at 14 years old in 1899 his father used the family connection to get him a job in the office at Sough Bridge Mill. This was a big mistake because Johnny didn’t like it one bit. As a lad he had spent a lot of time with his Uncle Jim round the engine at Sough and knew exactly what he wanted to do, be an engineer. I get the idea that it wasn’t the engines themselves that fascinated him but the size and complexity of the engineering which produced them. He liked the engines and understood them but his first love was always the skills needed to make them and other artefacts. His father persevered for almost four years trying to get Johnny to settle to a managerial life but he kept running away to his Uncle Daniel’s in Lothersdale. We don’t know what transpired, no doubt there were some stormy scenes and perhaps Daniel interceded for the lad. What is certain is that in 1903 William gave in, at the age of 18 years Johnny got his way and was apprenticed to Henry Brown, machinist and engineer, of Albion Street Earby. Our story is beginning to come together! (Newton Pickles told me that the man who William Pickles went to see at Earby was old William Brown “who started the firm in the first place” and Newton said that this was in 1887 which is two years earlier than the date on the sign at Wellhouse but as we have noted, he was in business before then.)

Johnny did three years apprenticeship at Browns and was then judged fit to be a journeyman. This was quick progress, he must have been an able pupil. The custom was that once an apprentice finished his initial tuition he went on the road to gain more experience at different firms. Johnny knew where the action was in the trade at that time so in 1906 he aimed himself at Lancashire and was immediately set on at Victory ‘V’ in Nelson as a maintenance engineer. They must have wondered what had hit them.

The first job they gave him was to make a guard for the gas engine that drove the machinery to make the famous throat lozenges. Johnny went to the lathe to make some studs and the cutting tools were worn out, he told Newton “They looked like shovels!” He asked the manager if there was a smith handy who could draw the cast steel tools out and re-temper them but the manager told him that they were good enough for the previous engineer so they would have to be good enough for him. Johnny immediately gave his notice and said he’d finish at the end of the day.

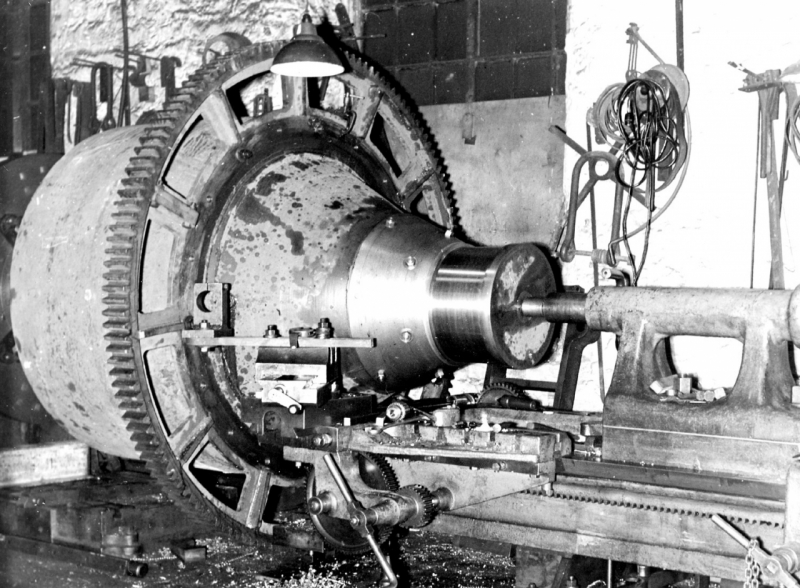

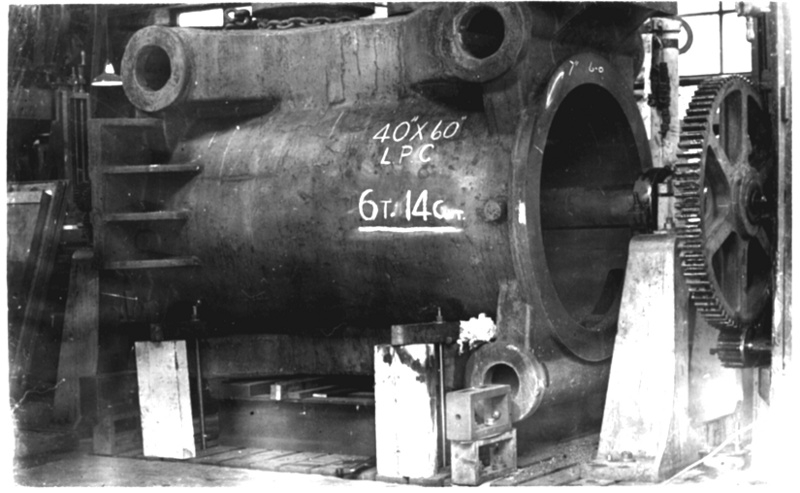

While this was going on the gas engine which drove the factory broke down and everything stopped. Johnny went to it and found the trouble, he took the cylinder head off, straightened the valves up and got it running again. That evening the manager from Victory ‘V’ went over to Kelbrook to ask Johnny to re-consider and go back but he refused. The following day he went to Burnley Ironworks to see the manager Mr. Metcalfe and ask him for a job. Mr. Metcalfe asked where he had served his time and when he heard it was Browns at Earby he set Johnny on straight away turning muff couplings for shafting. Before he had been there a week he was about thirty couplings in front of the man who was boring them and so the foreman put him on a brand new 4ft faceplate lathe making the eccentrics for the new engine for Brook Shed in Earby (750hp, installed in 1907). Eventually Johnny turned the governor stand and the connecting rods as well for that engine and always had a soft spot for it.

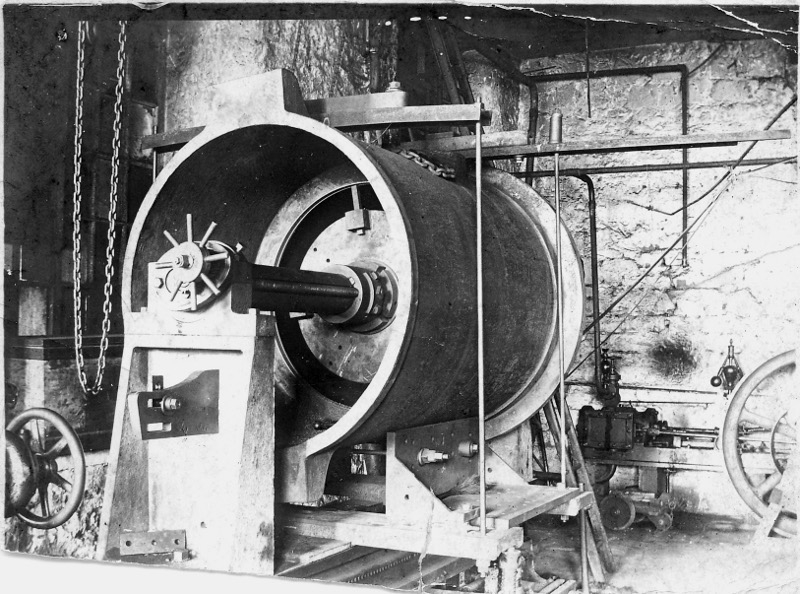

When he had finished this he was put on the wheelpit turning a new flywheel for an engine at Rawtenstall which had run away and had a smash. He did six weeks on nights at that job, it was a big flywheel. He said it did one revolution every two and a half minutes and they turned the 25 grooves in it with two and a half inch square chilled cast iron tools made from the same metal as the wheel. (A piece of information about a technique I have never found elsewhere and a good example of how vital it is to get close to the source) After that job finished he went back on turning bevel wheels. At this point Johnny looked set for a career at Burnley Ironworks, the best engine makers in the area.

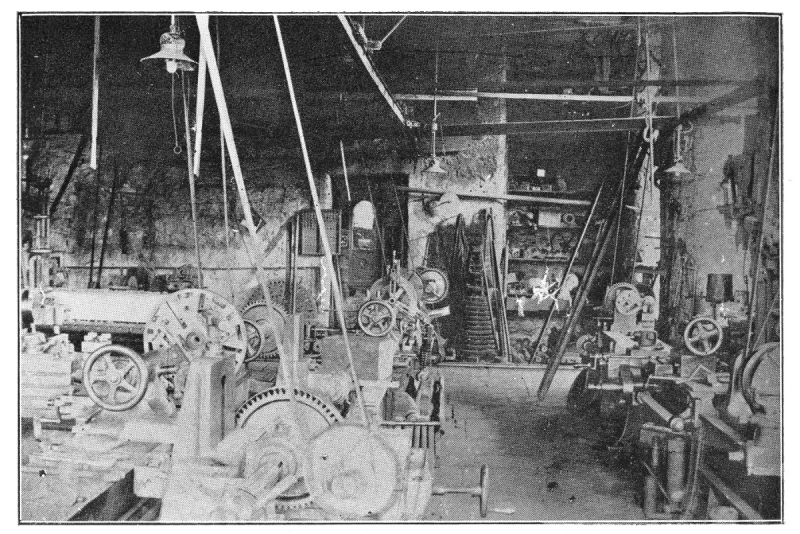

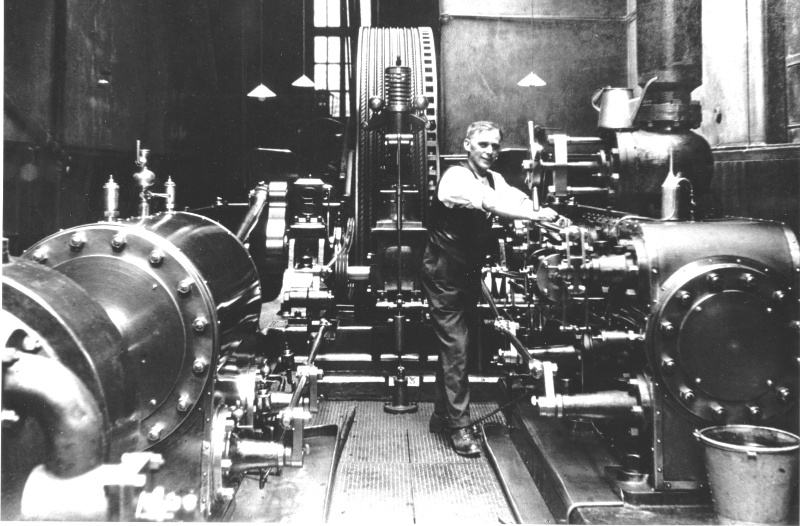

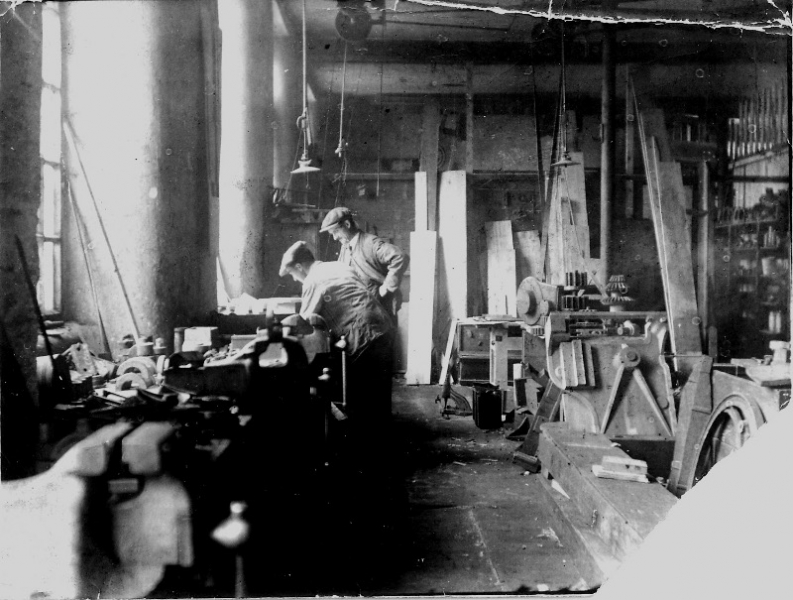

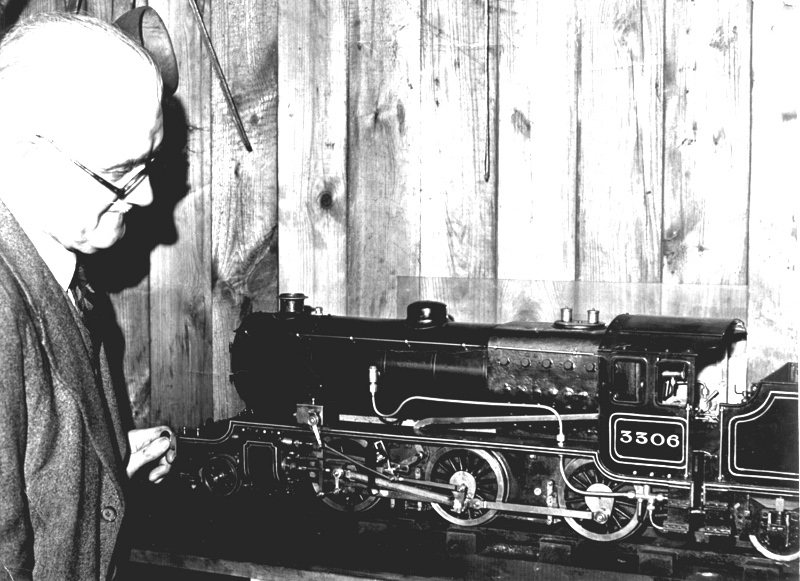

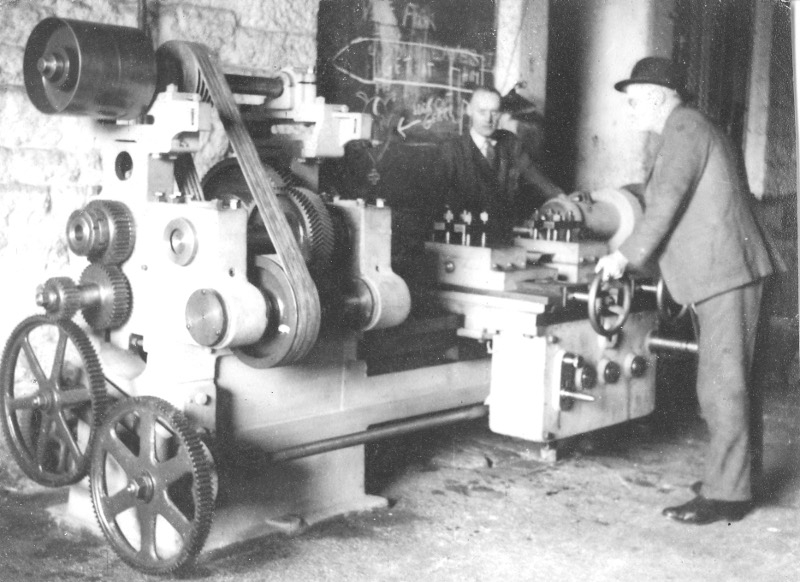

The young John Albert Pickles in Henry Brown's machine shop in Earby in 1903.