This was the crunch point, I had to think on my feet and produce an answer. Straight off the top of my head I gave them the following plan. Even now I am amazed because in the end, with one exception and one hold-up, neither of which were foreseeable, it was exactly what we did. Tony Welton never forgot it and when he finished at Coates he said it was the one thing he always remembered about that first meeting, the fact that I got it right first time without any preparation. That has always pleased me.

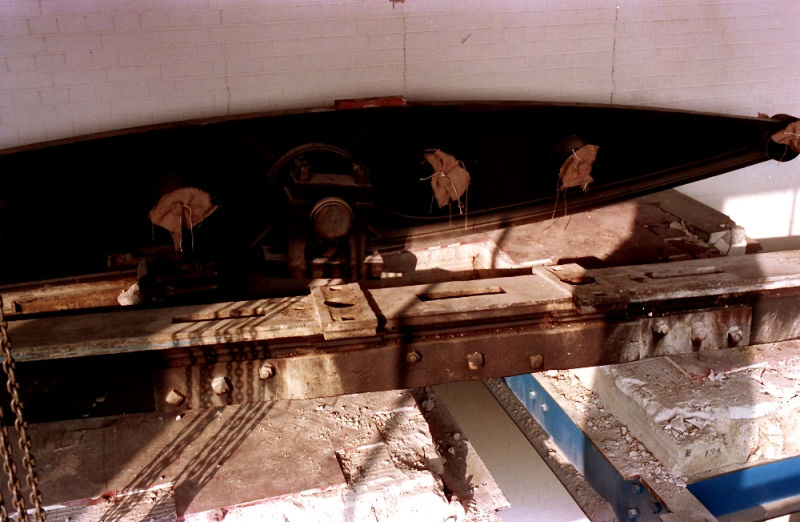

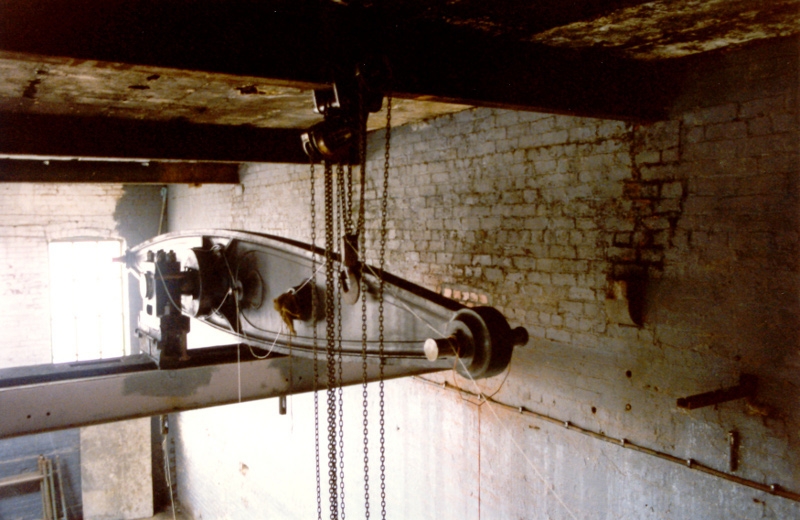

“The first thing we have to do is to assess what we have, decide whether it can ever run again, steam it to make certain and then get out a costed plan of what actually has to be done to the buildings and the artefacts. Next we have to get the local council on board and involve them, we will need a steering committee in the first place and the seats should be equally divided between the council, Coates and English Heritage as major funders. Then we have to set up a charitable trust as a company limited by guarantee and sort out a management structure. Once we have these elements in place and ownership of the site settled we have to start a programme of works, all arms of which have to proceed in parallel. We make the place safe and secure, we re-furbish the whole of the machinery and the buildings, we form a Friends Organisation and train them to run the engine, we build an external facility which will hold all the services necessary to run the engine house as a visitor attraction and finally, we recognise that the engine house will always lose money and therefore eventually we need a facility which includes fifty bedrooms, and all the necessary facilities to hold weekend study conferences primarily aimed at steam technology but doing anything else which will bring money in and visitors to the site. This last can wait on the back burner until we have all the rest in place, however, we need to set up an interpretative team straight away to start to gather the materials we will need to interpret and teach on the site.”

Tony pulled me up at this point and I can remember that at the time we were in the old board room of the mill, “Correction Stanley, the study facility is, in the final analysis, the key to the whole operation. It goes on in parallel with the rest.” He was the only person apart from myself who ever saw the importance of that element. Apart from me nobody else ever mentioned it again.

They withdrew for a moment and then came back. “How much do you need to make this work?”. I said that before I answered that question I’d want a couple of months to assess the place, then I’d have enough information to give some concrete opinions and blue sky figures. They agreed to pay me while I assessed the project, we decided that this had to be done before the end of February 1985. They also asked for some references so I went home with a job and a lot to think about. I got on to my friends and asked them to put a word in, DJ, David Sekers, John Robinson and Robert, they all sent letters of recommendation to Coates and eventually Coates informed me that subject to the results of the assessment of the site they would like to have me on board. Yippee! I went home, rang Robert and had a good drink!

You may be puzzled as to why I advised scrapping the engine. Looking back, I am convinced that my mind was in overdrive that day, it was exactly the right thing to say at the time. I had been asked to go down to Ellenroad and advise them as to what they should do. In terms of their business, scrapping the engine was the most economical, effective and certain way of dealing with the problem. Remember that I didn’t know anything about possible linkages with the council at that time, all I knew was that we were looking at the biggest single heritage problem in Britain at the time. Therefore, my advice was sound and absolutely in line with what I had been asked. In addition, there’s nothing like disarming criticism! If the project was to go ahead, I wanted to be able to say to them at some time in the future when things got sticky, “Remember what I told you in the engine house?” The occasion did arise a couple of times and my reminding them of this was always a show stopper! In case you’re wondering what I would have done if they’d said yes, even I don’t know the answer to that one, I suspect I’d have gone into salesman mode and sold them the project. However, as you’ll see later, I was quite capable of scrapping artefacts as big as this but the Dee Mill saga belongs to a later chapter!

This is as good a place as any to divulge one of my favourite and most effective weapons in the constant fight to get my own way! The morning after my meeting with Coates at the mill I wrote both Tony and Gavin a letter. This was something I had learned from David Moore. When you have had a verbal exchange with some party, either a meeting, a telephone conversation or any circumstance in which the details of the transaction weren’t recorded at the time, send them one of these letters. You always start by thanking them for the time they gave to have the meeting or call, specify the date and time. The next paragraph always starts; ‘My understanding of what we agreed is……..’ Then give a list of points, you can cheat a bit here and insert anything you wanted or delete anything you didn’t like. Also you can word the description of the point to give it the emphasis you want. After the list the final paragraph always says; ‘If your understanding varies from my own, please let me know by return of post.’ What you have done is put the ball squarely in their court. You have told them exactly what you are going to do and unless they get their act together and write back immediately they haven’t got a leg to stand on in any dispute. The reason why so many people conduct important business by telephone is because they don’t want any evidence that can pin them down. Another point is that most people’s comprehension of the written word is so bad that they won’t recognise that what you are doing is modify the agreement to suit yourself and in any case, in nine cases out of ten a beaurocrat won’t bother to do anything other than acknowledge the letter. I promise you, this works like a charm. Another associated ploy is that whenever you have a telephone conversation, keep a file note of the time, date, person’s name and a brief account of what was said. This can be invaluable when the shit hits the fan.

Associated with this subject is the concept of the ‘Pearl Harbour File’. Susi told me about this one and it’s a cracker. Always keep copies of memoranda and letters in a personal file of your own. This is your property and you keep it at home. Always plan for worst case and if and when you need it, a PHF can be a killer! I have to admit I have been known to send memoranda with nothing but a PHF in mind. The technical term for this is ‘Covering Your Arse!’. Once again, people are idle and don’t read things. When the storm comes and someone denies having known something you just wave the piece of paper at them and they fall over.

Back to the job in hand. Winter was upon us and as I pondered about how to attack the assessment of Ellenroad I learned from Gavin that Coates had a serious deadline. In order to qualify for a large grant, they had to have the factory built and producing by November 1985 so they had to start on the demolition. He asked me if I had any recommendation as to who to set on. I told him to speak to N&R at Portsmouth Mill, Todmorden and ask for Norman Sutcliffe. N&R had demolished Bancroft and I liked them. Like all demolition contractors they were a slippery lot but they had the tackle and did a good job. Gavin went off and did his homework and shortly afterwards told me he liked my choice, he had had a look at one or two firms but had settled on N&R who had agreed to do the job for a demolition credit of £50,000.

A word of explanation here. The demolition credit is the amount the contractor pays to the owner of the building for the privilege of knocking it down and becoming the owner of any plunder. The main source of income for N&R out of this job was any cut stone and metal they salvaged out of the structure. Gavin was pleased with the price he had negotiated but I told him to beware. I said that from my experience he had better regard this money as a short term loan from N&R because Norman was as cute as a barrow load of monkeys and would get it back out of him in extras. Gavin bridled a bit at this, he informed me that he was used to negotiating and there was no way he would allow Norman to get away with anything. I got the definite impression that he had under-estimated Norman and so left it at that!

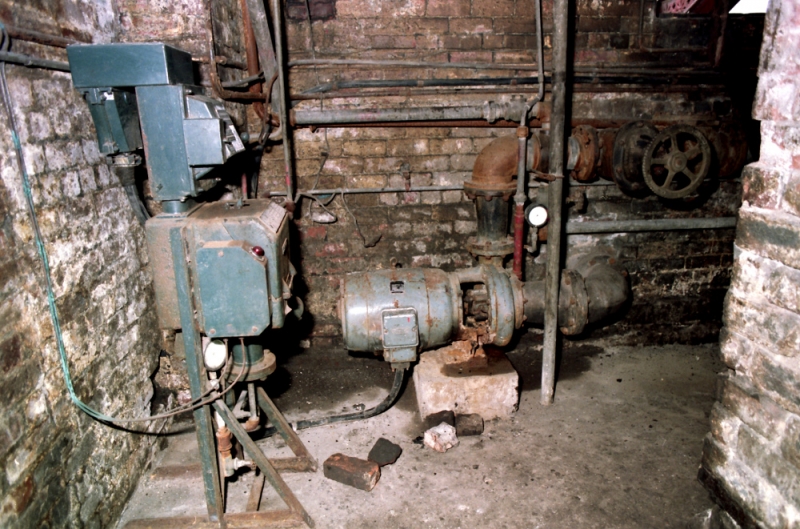

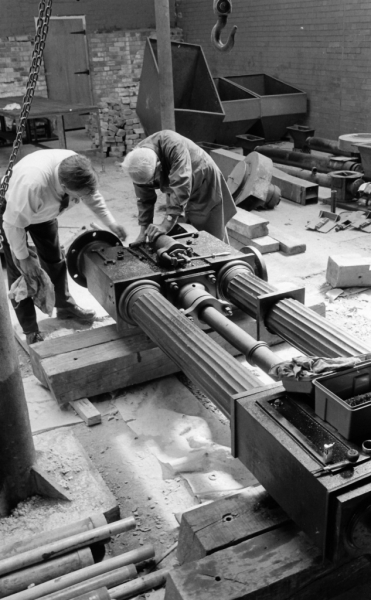

I started the assessment in January 1985 and at about the same time N&R moved on to the site to demolish the mill. A lot of things happened at once here so I’ll split them up and tackle what I had to do as regards the engine house first. I should add that Coates asked me to act as their agent in the matter of the demolition and advise them as it went on so I was doing my own thing and liaising with N&R at the same time. This was a good thing as it gave me access to the N&R cabin for a warm and a brew whenever I wanted it. It also helped me to get a better idea of what demolition actually entailed which was an education.

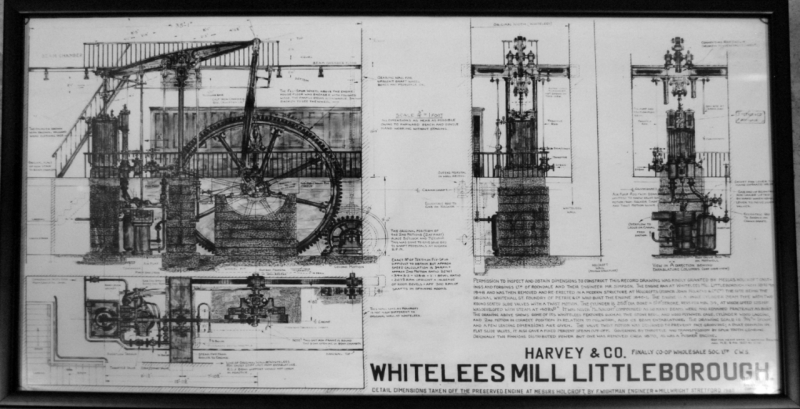

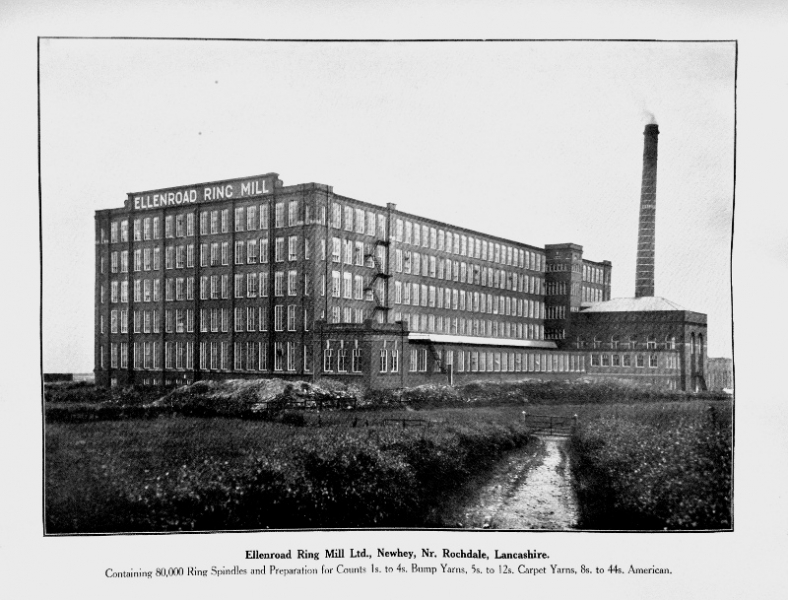

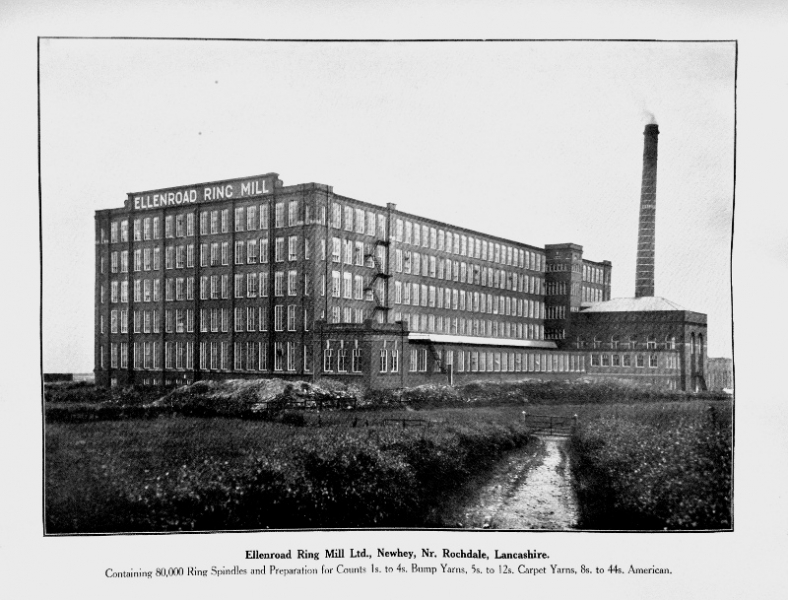

A 1929 pic used as advertising by Platt Brothers who equipped the original mill. Essentially this was what I was faced with.