Thanks for a great explanation. Sorry, I didn't mean to cause you so much work.

STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

Thanks for a great explanation. Sorry, I didn't mean to cause you so much work.

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

China, you're welcome and that wasn't a 'lot of work'. It was a labour of love and all out of my head, I just wrote for half an hour. It's a pleasure to be asked a question and have an excuse to pass on some of the stuff I have picked up in many years of experience and enquiry.

So ask questions!

So ask questions!

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

Back to mistakes I have seen. Have a look at this for the latest on the Smith and Eastwood engine that ran Peter Green's mill at Bradley.

I went with Newton one day to see this engine running, it had been in Newton's care for years. We were looking at it when the firebeater came in and reported he had no water level in his gauge, he wanted to know what to do. Neston sent me into the boiler house with him and when we got in there he was right, he had no visible level and had assumed that this meant there was no water in the boiler. He asked me whether he should put the feed pump on at full bore but I told him to hang on because I suspected I knew what was wrong. I blew his gauges down and found I was right, he hadn't got low water, the reason he couldn't see a level was that it was above the sight gauges and putting the feed pump on was the last thing he should do. Steam engines don't like water going in the cylinders, this has wrecked many engines. (Look back in the topic to what happened at Crow Nest when they got a slug in the low pressure) I told him to close the feed valve to make sure no water was going in the boiler. I did this because I didn't know his source and in some instances the pressure on the water main is higher that the working pressure of the boiler, this was common in the Tod Valley. Then we opened the blow down valve a crack and I told him to watch the gauge and let us know when he was an inch below the top of the glass.

I went back in and reassured Newton who of course had suspected this all along. The engine was running OK and not picking up carry over. This can happen sometimes with high water level if the boiler water is dirty and has foam on top of it. This why Lancashire boilers always have a perforated separator at the entrance into the junction valve.

This mistake was a common one if a firebeater wasn't paying attention to what his gauges were telling him. A good man checks the level all the time and never gets into this position but the action is obvious, blow the gauges down and you'll soon get a true picture.

If he had been right and there had been low water there is no need for immediate panic because the water level at the bottom nut on the gauge is still at least 2" above furnace crown level which, whilst not ideal, isn't dangerous.

Many boilers, as at Bancroft, had a low water and high steam alarm. This was a secondary safety valve which had a float suspended below it and under normal conditions this put no weight on the valve and it stayed closed. If the water level dropped it opened the valve and steam was let off giving a warning that something was wrong. Some had a whistle connected to the exhaust pipe, Bancroft didn't have this. The high steam element of the valve was that as a normal lever and weight safety valve it was set for 5psi above red line and if the dead weight valve couldn't cope with the pressure in high firing conditions it opened and relieved any excess that was building up. Incidentally, the low water float was a bugger to adjust. We all had our favourite methods but in truth not many low water valves functioned correctly. I never touched the one on Bancroft boiler and it always functioned well. The test was when we were emptying the boiler for annual maintenance you opened the blow down and noted whether the low water valve functioned correctly.

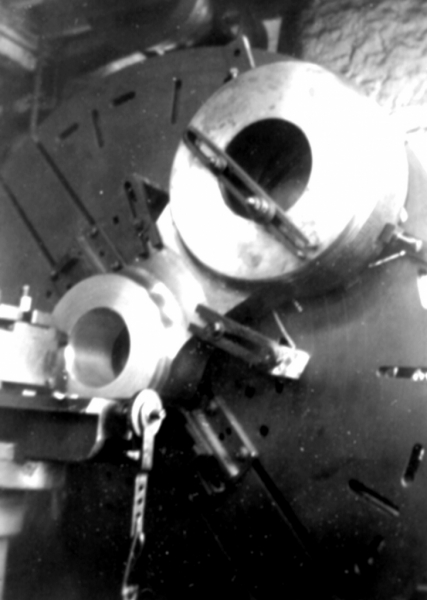

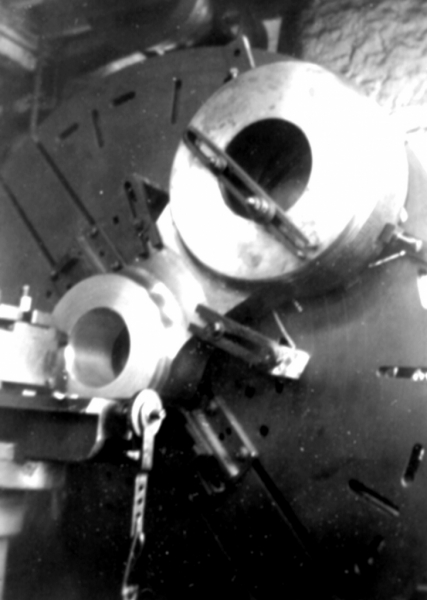

The high steam/low water valve at Bancroft.

I went with Newton one day to see this engine running, it had been in Newton's care for years. We were looking at it when the firebeater came in and reported he had no water level in his gauge, he wanted to know what to do. Neston sent me into the boiler house with him and when we got in there he was right, he had no visible level and had assumed that this meant there was no water in the boiler. He asked me whether he should put the feed pump on at full bore but I told him to hang on because I suspected I knew what was wrong. I blew his gauges down and found I was right, he hadn't got low water, the reason he couldn't see a level was that it was above the sight gauges and putting the feed pump on was the last thing he should do. Steam engines don't like water going in the cylinders, this has wrecked many engines. (Look back in the topic to what happened at Crow Nest when they got a slug in the low pressure) I told him to close the feed valve to make sure no water was going in the boiler. I did this because I didn't know his source and in some instances the pressure on the water main is higher that the working pressure of the boiler, this was common in the Tod Valley. Then we opened the blow down valve a crack and I told him to watch the gauge and let us know when he was an inch below the top of the glass.

I went back in and reassured Newton who of course had suspected this all along. The engine was running OK and not picking up carry over. This can happen sometimes with high water level if the boiler water is dirty and has foam on top of it. This why Lancashire boilers always have a perforated separator at the entrance into the junction valve.

This mistake was a common one if a firebeater wasn't paying attention to what his gauges were telling him. A good man checks the level all the time and never gets into this position but the action is obvious, blow the gauges down and you'll soon get a true picture.

If he had been right and there had been low water there is no need for immediate panic because the water level at the bottom nut on the gauge is still at least 2" above furnace crown level which, whilst not ideal, isn't dangerous.

Many boilers, as at Bancroft, had a low water and high steam alarm. This was a secondary safety valve which had a float suspended below it and under normal conditions this put no weight on the valve and it stayed closed. If the water level dropped it opened the valve and steam was let off giving a warning that something was wrong. Some had a whistle connected to the exhaust pipe, Bancroft didn't have this. The high steam element of the valve was that as a normal lever and weight safety valve it was set for 5psi above red line and if the dead weight valve couldn't cope with the pressure in high firing conditions it opened and relieved any excess that was building up. Incidentally, the low water float was a bugger to adjust. We all had our favourite methods but in truth not many low water valves functioned correctly. I never touched the one on Bancroft boiler and it always functioned well. The test was when we were emptying the boiler for annual maintenance you opened the blow down and noted whether the low water valve functioned correctly.

The high steam/low water valve at Bancroft.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

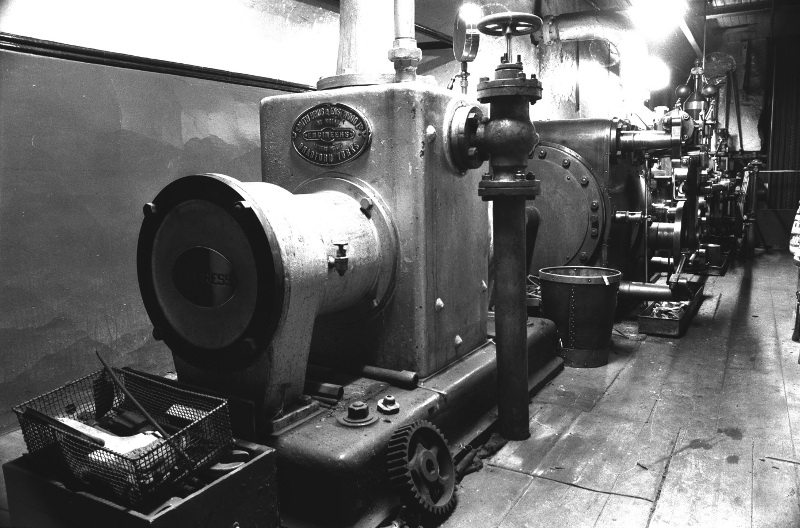

The engine as originally installed at Bradley.....

Another example on a bigger engine.....

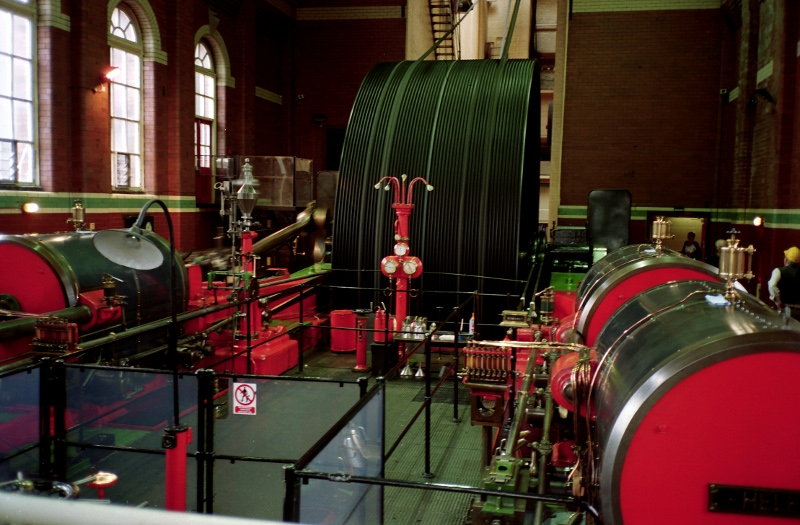

The Trencherfield mill engine at Wigan Pier. It was owned and run by Wigan Metropolitan Council who had sub-contracted the management of the boilers and engine to a firm called Associated Heat Services. They had a name change to Dalkea and REW did much of their repairs. Here’s one last conservation matter for you. In 2000 John Ingoe called in at Barlick for tea and brought Vanessa and Alex. Just as they were leaving he asked me if I’d like a trip out to Trencherfield at Wigan Pier, he had a contract to fit some oil drip trays and there was a problem with the barring engine. I said yes and we went over there on July 5th, I should add that this was with the full knowledge of Steve Redfern who was Dalkea’s site manager. Dalkea was the new name for Associated Heat Services and they ran all Wigan MBC’s boilers and steam plant for them. Part of his responsibility was the Trencherfield Mill Engine which was run daily for visitors.

When we got there I watched the barring engine running, identified the fault and told them what to do about it. Privately, I told John what I suspected the real fault was, they had piped the drains and exhaust into a system that was putting back pressure on the engine. This turned out to be correct but that was that, problem solved.

While I was looking at the engine I pointed out to Steve that the stakes were bleeding in the LH flywheel, a sure indication that they were slowly coming loose. He didn’t understand what I was talking about so I explained fretting corrosion to him and the fact that the red oxide mixed with oil bleeding out of the stake beds was a consequence of this. I told him it wasn’t desperate but he should take note as it wouldn’t get any better. While I was there I would have a look at the other side on the RH flywheel. (On a big engine like Trencherfield there are usually two flywheels mounted next to each other.) I walked round, took a look and told him he had to stop the engine immediately, or rather not run it any more. The RH flywheel was rolling off its stakes and had been in trouble for a long time. What I mean by this is that it had moved on the wedges that held it on the shaft and was only jammed on the edge of the stakes. It was very dangerous and they had parties of schoolchildren walking within ten feet of it!

I’ll gloss over a lot of what followed, basically Steve didn’t want to know, he wanted a quiet life. His first reaction was to ask me what my qualifications were. I told him I had none only experience but this didn’t matter. Even if I was a copper-bottomed certified lunatic he had to take note of what I said and investigate it. On the other hand, as I pointed out to John on the way home, he and I were under a duty of care and I had to send him a report which he must forward to Dalkea. John agreed, I did this, he passed it on to Dalkea and the brown stuff hit the fan. Steve had to pass it to the council and they acted immediately to stop the engine. I was banned from all Dalkea sites for ever, John was threatened with commercial implications as much of his work was with Dalkea, in short, it all got very nasty. Give John his due, he knew what had to be done and had the moral courage to do it. I left them with one uncomfortable thought, if they started running the engine again in that condition my duty of care would be revived and I would only have one recourse, to blow the whistle to the Health and Safety Executive. This would really put the cat amongst the pigeons because the whole field of running engines for the public is a minefield and if the HSE really looked into it they would shut many of them down. Let’s put it this way, if I was in charge I’d shut many down immediately pending certain safety measures. Take it from me, they wouldn’t like it.

Give Wigan MBC their due, they took action. I was asked down again to advise the council by Emma Birkin, the lady who was in charge of the project. They were pleased with my advice and impressed by the fact I had knowledge that didn’t exist inside the council. I pointed to other problems like a loose die block on the LH HP valve gear and the dangers of running at half speed. I never charged them for my time but asked for travelling expenses. It took a letter to the Chief Executive to get this money after two years! I have an idea that I upset them when I pointed out that the large amount of money they had spent previously to prevent oil getting into the canal had been wasted. All they needed to do was run all the drains into a jack well which would have caught all the oil on the surface.

I put them in touch with Gissing and Lonsdale at Barnoldswick who tendered for re-staking the flywheel, taking advice from me. This never came to anything and the next news I received was a copy of an inspection that had been done on the engine by Doctor Jonathan Mimms of the English Engineerium at Brighton. I don’t know the man but it is obvious from his recommendations that he has theoretical knowledge of steam engines but has never run one commercially. The measures he proposed were extreme and if carried out would result in the most dangerous engine in Britain. I contacted the Council and told them this but they didn’t want to know. I sent a written statement of my opinion so that I had discharged my duty of care and after this was acknowledged forgot all about it. The council took what they saw were the correct actions and as far as I know the engine has been rectified and is running safely.

This brings up a few related matters. The first is the danger of taking the advice of people who only have theoretical knowledge. The only reason most engines in preservation run safely is because there is enough wear in the bores to allow any condensate to escape on compression. Don't forget that all these engines run too cold because they are in effect idling. This means that they generate more condensate than in their working life. Re-boring such an engine and restoring full compression increases the danger of a slug and its consequences.

The fact that they were running the engine and hadn't noticed that one half of the flywheel was almost off its stakes and that one of the die blocks on the Dobson motion on the RH HP cylinder was loose points to lack of informed inspection.

Most important was the speed they ran the engine at. If you think of a 90ton flywheel sat on a a 30ft steel shaft it's obvious it will bend it. The old manufacturers knew this and arranged the speed of the engine so that centrifugal force stabilised the wheel and the shaft stayed straight while running. The only time the shaft flexed was at starting and stopping. Running engines at half speed in the interests of safety means that the shaft is constantly flexing and we all know how to break a piece of wire. I argued this with English Heritage and the insurance companies and that's why Bancroft and Ellenroad run at their designed speed.

The bottom line is that the books can't give all the answers, you need a bloke like Newton to teach you!

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

One of the problems about getting into a subject as deeply as I have with engines and boilers is that you end up putting some people's backs up because you tend to sound like a know-all. I can assure you that I don't see myself that way, it just so happens that I am an inquisitive bugger and always want to know more. Then, as Daniel Meadows once said, I have this compulsion to pass on what I have learned. That's why I bother with posts like this, the biggest problem we have is that so often people learn so much and fail to pass it on. Sorry about that, that's my story and I am sticking to it!

When we wove out at Bancroft it was a bad experience and I'll admit that for a time I was angry, if anyone approached me my attitude was bugger steam engines and boilers but of course the pull was too strong and one man in particular understood and quietly brought me back to reality. That was Les Say who was manager of Rolls Royce in Barlick. He persuaded me to join in the effort to save Bancroft engine as a heritage attraction and the crafty bugger arranged it so that I was the new Trust's first chairman. I had to give that up when I went to university but even there the engines pursued me. When we got to the section of the Economics course dealing with the advent of steam they asked me to do the lectures! The bottom line is that I found I quite enjoyed passing knowledge on and eventually wrote my books in an attempt to empty my head. I made a start but I haven't managed it yet.

As I got more and more involved with preservation mainly at Bancroft and then at Ellenroad, I had a lot of contact with English Heritage and The Science Museum and occasionally they asked me to inspect and report on attractions which had applied for grants. I tried to do it honestly and at times it seemed to cause nothing but trouble. I went to one well known plant in the West Country that ran their engine for the public and pointed out to them that they had disabled the only safety feature the engine had and were in danger of an overspeed at any time. I had a lot to learn and I became 'He whose name must not be mentioned'! I don't know what happened eventually but they are still in business and running the engine.

I saw the possible dangers at Ellenroad..... I'll tell you what I did and what happened tomorrow.

When we wove out at Bancroft it was a bad experience and I'll admit that for a time I was angry, if anyone approached me my attitude was bugger steam engines and boilers but of course the pull was too strong and one man in particular understood and quietly brought me back to reality. That was Les Say who was manager of Rolls Royce in Barlick. He persuaded me to join in the effort to save Bancroft engine as a heritage attraction and the crafty bugger arranged it so that I was the new Trust's first chairman. I had to give that up when I went to university but even there the engines pursued me. When we got to the section of the Economics course dealing with the advent of steam they asked me to do the lectures! The bottom line is that I found I quite enjoyed passing knowledge on and eventually wrote my books in an attempt to empty my head. I made a start but I haven't managed it yet.

As I got more and more involved with preservation mainly at Bancroft and then at Ellenroad, I had a lot of contact with English Heritage and The Science Museum and occasionally they asked me to inspect and report on attractions which had applied for grants. I tried to do it honestly and at times it seemed to cause nothing but trouble. I went to one well known plant in the West Country that ran their engine for the public and pointed out to them that they had disabled the only safety feature the engine had and were in danger of an overspeed at any time. I had a lot to learn and I became 'He whose name must not be mentioned'! I don't know what happened eventually but they are still in business and running the engine.

I saw the possible dangers at Ellenroad..... I'll tell you what I did and what happened tomorrow.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

At Ellenroad we were dealing with a big engine. The capacity for a disaster was also bigger! I never forgot the overspeed that Newton and I triggered when we ran the engine for the first time, I can tell you that watching an 86ton flywheel rotating at twice its designed speed grabbed your attention!

We tried to do everything to top standard at Ellenroad and the first thing I did when we were re-commissioning the boiler was to win two electric feed pumps and install them as the main feed resource in addition to the two steam pumps, a Weir and a German one that Budenberg's at Sale gave me. Once we had electric pumps we had the possibility of automatic water level control. I had won some Mobrey sensors, they are still in business. You fitted two of them on the boiler front which involved getting REW in to make two 'stab ins', cutting holes in the front plate and welding connections on to them. One monitored high water and one low and they were connected to a control box and an indicator with four coloured lights on the boiler front that indicated the water condition. There was a siren to act as an audible warning and these two controls managed the feed pumps, you could adjust the sensitivity to any desired level and also the 'dwell', the latitude they allowed before kicking in. There was a repeater panel in the engine house so the engineer could see at a glance what the state of his water levels was in the boiler. Allied to the pressure control on the boiler which controlled the automatic stokers this meant that in theory, as long as the hoppers on the stokers were full, steam raising was automatic. We didn't go this far we always had someone in attendance on the boiler, our aim was to have a system that gave warning if something was wrong because we were of course using volunteers who weren't quite up to the standards of professionals. We had done all we could to make the system fail-safe.

English Heritage and the insurance company appreciated all this and I felt safe, I had done all I could. In the days when my beard was black I once had to spend two hours in the witness box at Leeds Crown Court in a commercial dispute and I never forgot it. When we were doing anything I always reminded my people that they should always consider the possibility that if there was an accident they might have to stand in the box at an inquest. The first thing was to do everything possible to avoid this eventuality but if that happened they would be a lot more comfortable if they could prove this.

I took my own advice and started to mull over the safety of the engine itself.......

We tried to do everything to top standard at Ellenroad and the first thing I did when we were re-commissioning the boiler was to win two electric feed pumps and install them as the main feed resource in addition to the two steam pumps, a Weir and a German one that Budenberg's at Sale gave me. Once we had electric pumps we had the possibility of automatic water level control. I had won some Mobrey sensors, they are still in business. You fitted two of them on the boiler front which involved getting REW in to make two 'stab ins', cutting holes in the front plate and welding connections on to them. One monitored high water and one low and they were connected to a control box and an indicator with four coloured lights on the boiler front that indicated the water condition. There was a siren to act as an audible warning and these two controls managed the feed pumps, you could adjust the sensitivity to any desired level and also the 'dwell', the latitude they allowed before kicking in. There was a repeater panel in the engine house so the engineer could see at a glance what the state of his water levels was in the boiler. Allied to the pressure control on the boiler which controlled the automatic stokers this meant that in theory, as long as the hoppers on the stokers were full, steam raising was automatic. We didn't go this far we always had someone in attendance on the boiler, our aim was to have a system that gave warning if something was wrong because we were of course using volunteers who weren't quite up to the standards of professionals. We had done all we could to make the system fail-safe.

English Heritage and the insurance company appreciated all this and I felt safe, I had done all I could. In the days when my beard was black I once had to spend two hours in the witness box at Leeds Crown Court in a commercial dispute and I never forgot it. When we were doing anything I always reminded my people that they should always consider the possibility that if there was an accident they might have to stand in the box at an inquest. The first thing was to do everything possible to avoid this eventuality but if that happened they would be a lot more comfortable if they could prove this.

I took my own advice and started to mull over the safety of the engine itself.......

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

We were accident free at Ellenroad on site and no problems with the engine because I was always there when it was running. In fact for about two years I ran for the public on my own every Saturday while I trained my volunteers up. It was hard but I used to console myself at 4AM on a winter morning as I was going to Ellenroad that many people would give their eye teeth to be able to play with a 3,000hp steam engine!

Always at the back of my mind was the fact that at some point the volunteers would be on their lonesome and enthusiasm is not the same as years of experience so I started plotting. Lots of thought and consultation and I came up with a scheme whereby I could install safety measures on the engine. English Heritage were very enthusiastic because they could see the dangers and they said that once it was up and running they would write it up and issue it as an advisory document for other venues.

There were three main parameters to consider; speed, boiler pressure and vacuum. Speed was easy, we had the teeth of the barring rack on the inside edge of the flywheel so we installed a sensor close to the wheel that detected the passing of the teeth which gave us a very accurate reading. Boiler pressure was also simple, we simply linked into the Mobrey valves and warning lights that we had already installed on the boiler. Vacuum was a simple sensor in each of the feeds to the vacuum gauges. In all of this I had the support of a firm in Rochdale who advised me on the technicalities and gave us the magic box of eproms that would interpret the input and could be set to whatever parameters we wanted to apply, that was installed and still sits on the wall in the engine house. That took care of detection, input and actuation but I had to address how we were going to enable the system to stop the engine if any of the parameters went out of range. That was down to me and I went begging! The first thing I got was a free electrically actuated 6" steam valve that we inserted into the main steam pipe. Then I found a vacuum breaker valve that worked by being kept closed by air pressure on a diaphragm and could be actuated by a valve closing in the compressed air line. We fitted that but until we got the compressor I kept it closed with a large nut trapped under the lid!

All this was done in the run-up to getting the Whitelees beam engine running so I was thronged. I got to the stage where all we needed to do was install the compressor, wire the system up and commission it. At that point I had to concentrate on the Whitelees and so put the safety system on hold. It was all there, the work had been done, all it needed was a small investment in the compressor and the free work of the firm that had helped with the magic box.

The best laid schemes of mice and men.... At this point, after the successful commissioning of the Whitelees the Trust ran out of money because I had had to put fund-raising on hold, I was too busy. The upshot was that the Directors had a crisis of confidence and decided they could dispense with my services as they had a running engine and trained volunteers but no money to support me. They completely forgot what remained to be done. So I departed for pastures new, the other parts of the original Ellenroad Project were forgotten and the safety system was never commissioned. To put it mildly it was a bit of a shame.....

Thirty years later.... as far as I know the system has never been actuated, English Heritage never wrote it up and it sank into the mists of history.

Always at the back of my mind was the fact that at some point the volunteers would be on their lonesome and enthusiasm is not the same as years of experience so I started plotting. Lots of thought and consultation and I came up with a scheme whereby I could install safety measures on the engine. English Heritage were very enthusiastic because they could see the dangers and they said that once it was up and running they would write it up and issue it as an advisory document for other venues.

There were three main parameters to consider; speed, boiler pressure and vacuum. Speed was easy, we had the teeth of the barring rack on the inside edge of the flywheel so we installed a sensor close to the wheel that detected the passing of the teeth which gave us a very accurate reading. Boiler pressure was also simple, we simply linked into the Mobrey valves and warning lights that we had already installed on the boiler. Vacuum was a simple sensor in each of the feeds to the vacuum gauges. In all of this I had the support of a firm in Rochdale who advised me on the technicalities and gave us the magic box of eproms that would interpret the input and could be set to whatever parameters we wanted to apply, that was installed and still sits on the wall in the engine house. That took care of detection, input and actuation but I had to address how we were going to enable the system to stop the engine if any of the parameters went out of range. That was down to me and I went begging! The first thing I got was a free electrically actuated 6" steam valve that we inserted into the main steam pipe. Then I found a vacuum breaker valve that worked by being kept closed by air pressure on a diaphragm and could be actuated by a valve closing in the compressed air line. We fitted that but until we got the compressor I kept it closed with a large nut trapped under the lid!

All this was done in the run-up to getting the Whitelees beam engine running so I was thronged. I got to the stage where all we needed to do was install the compressor, wire the system up and commission it. At that point I had to concentrate on the Whitelees and so put the safety system on hold. It was all there, the work had been done, all it needed was a small investment in the compressor and the free work of the firm that had helped with the magic box.

The best laid schemes of mice and men.... At this point, after the successful commissioning of the Whitelees the Trust ran out of money because I had had to put fund-raising on hold, I was too busy. The upshot was that the Directors had a crisis of confidence and decided they could dispense with my services as they had a running engine and trained volunteers but no money to support me. They completely forgot what remained to be done. So I departed for pastures new, the other parts of the original Ellenroad Project were forgotten and the safety system was never commissioned. To put it mildly it was a bit of a shame.....

Thirty years later.... as far as I know the system has never been actuated, English Heritage never wrote it up and it sank into the mists of history.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

3000hp = 2237 kW = 2.237 MW. At the chemical works where I worked we had a gas turbine (like a small jet engine driven by compressed natural gas) which generated 5MW of electricity = 6705 hp. It was a joy and simple to start up and ran automatically and largely unattended for years. We stopped for a couple of hours every 2 weeks to clean the turbine blades. The hot exhaust gasses were used to generate steam, about 25 tonnes per hour at 12 barg so it was extremely efficient. You can see why steam engines died out as new technology came along.

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

Yes China but not the Steam Age, we still use turbines now even when atomic power produces the heat to raise steam.

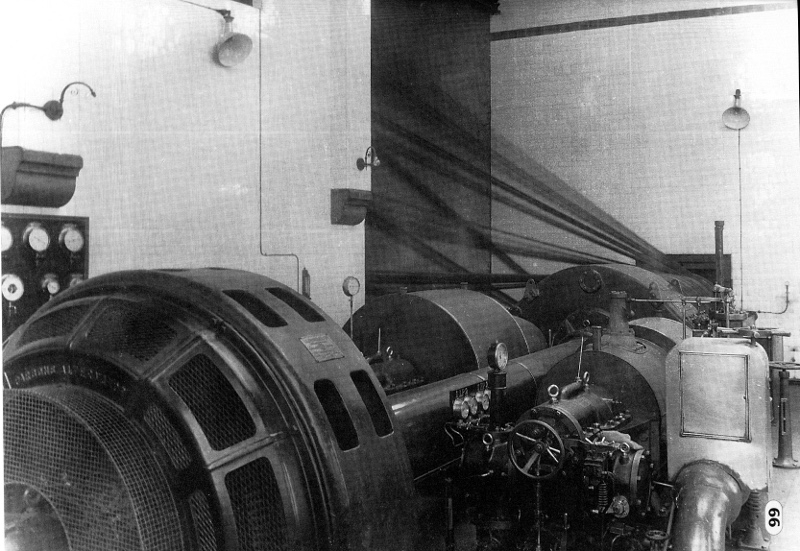

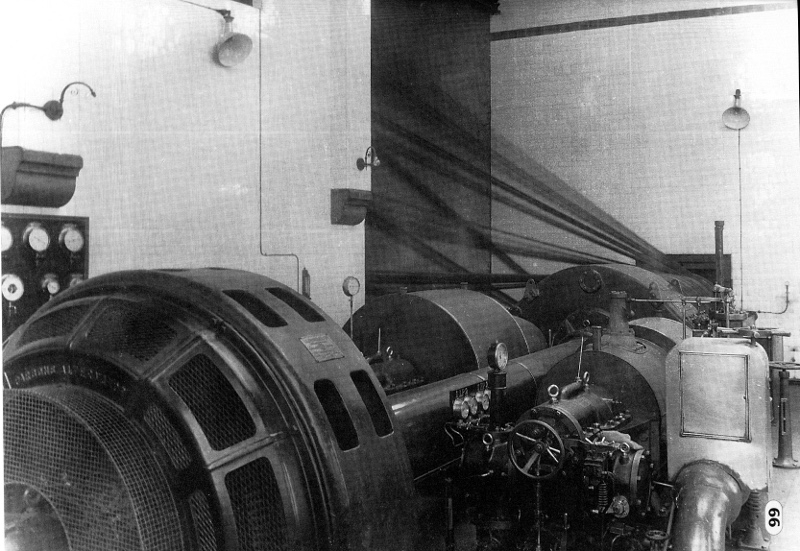

Some mills installed turbines, this one is at Elk Mill, Royton, part of Shiloh Spinners, in 1927. It drove the shafting in the mill and also an alternator producing electricity. Newton always wanted to install a turbine. When Bishop Gate smashed up he found a secondhand one and wanted to replace the engine but the management and the insurance company wouldn't sanction it.

Some mills installed turbines, this one is at Elk Mill, Royton, part of Shiloh Spinners, in 1927. It drove the shafting in the mill and also an alternator producing electricity. Newton always wanted to install a turbine. When Bishop Gate smashed up he found a secondhand one and wanted to replace the engine but the management and the insurance company wouldn't sanction it.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

The economics of running a steam engine to produce power.

Coates Inks owned the Ellenroad site and the Trust leased the engine house from them. I had always had a good relationship with them ever since the CEO, John Youngman, had decided to finance me to do a feasibility study on creating a heritage attraction and giving Coates the opportunity to get finance for the access road (I found this out later). In addition I monitored the demolition for them on a daily basis. Add to this the fact that I delivered on time and we had a running engine.

By about 1987 they had the ink factory up and running and I approached them and pointed out that electricity prices were rising and my experience at Bancroft had proved to me that with a fully written off plant and a large alternator in the cellar the engine could produce electricity at very attractive prices. They commissioned a study by their accountants who agreed and said that the scheme was viable and would result in a considerable saving. In the end the board decided against using the resource, not because the numbers were wrong but the complications of relying on the Trust to set in place staffing to run it. I understood why but it was an opportunity wasted.

Later John Ingoe came to me and asked about the economics, he had an enquiry from a firm he did boiler maintenance for about finding an engine and installing it on an alternator to make leccy. This firm had to run boilers for process steam and I convinced John that using spare capacity to run a modern engine on an alternator was a licence to print money because the expense of the boilers and heat losses were already absorbed by the business. The only extra expense was the extra fuel, the capital cost and staffing. The capital cost was minimal because good modern high speed engines were available at little cost. There was a big Belliss and Morcom high speed engine at Hill's Pharmaceuticals at Harle Syke that could be bought cheap. The firm in question did their sums and saw the advantages and I know it got to the stage where the engine was bought and taken out but what happened after that I don't know. I have an idea in the back of my mind that it was eventually exported to India.

The point of all this is that steam engines, even the old horizontal mill engines used far less steam than people thought and if a boiler had to be run anyway for process, the eventual cost of the leccy was about half price compared with the mains. Funnily enough, this point had been proved long before when manufacturers were being persuaded by the CEGB to ditch steam and go over to electric driving of looms.......

Coates Inks owned the Ellenroad site and the Trust leased the engine house from them. I had always had a good relationship with them ever since the CEO, John Youngman, had decided to finance me to do a feasibility study on creating a heritage attraction and giving Coates the opportunity to get finance for the access road (I found this out later). In addition I monitored the demolition for them on a daily basis. Add to this the fact that I delivered on time and we had a running engine.

By about 1987 they had the ink factory up and running and I approached them and pointed out that electricity prices were rising and my experience at Bancroft had proved to me that with a fully written off plant and a large alternator in the cellar the engine could produce electricity at very attractive prices. They commissioned a study by their accountants who agreed and said that the scheme was viable and would result in a considerable saving. In the end the board decided against using the resource, not because the numbers were wrong but the complications of relying on the Trust to set in place staffing to run it. I understood why but it was an opportunity wasted.

Later John Ingoe came to me and asked about the economics, he had an enquiry from a firm he did boiler maintenance for about finding an engine and installing it on an alternator to make leccy. This firm had to run boilers for process steam and I convinced John that using spare capacity to run a modern engine on an alternator was a licence to print money because the expense of the boilers and heat losses were already absorbed by the business. The only extra expense was the extra fuel, the capital cost and staffing. The capital cost was minimal because good modern high speed engines were available at little cost. There was a big Belliss and Morcom high speed engine at Hill's Pharmaceuticals at Harle Syke that could be bought cheap. The firm in question did their sums and saw the advantages and I know it got to the stage where the engine was bought and taken out but what happened after that I don't know. I have an idea in the back of my mind that it was eventually exported to India.

The point of all this is that steam engines, even the old horizontal mill engines used far less steam than people thought and if a boiler had to be run anyway for process, the eventual cost of the leccy was about half price compared with the mains. Funnily enough, this point had been proved long before when manufacturers were being persuaded by the CEGB to ditch steam and go over to electric driving of looms.......

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

Exactly the same reasons why CHP (combined heat and power) plants are so efficient and produce cheap electricity. In most thermal power stations like coal/oil/nuclear the waste heat is lost to the atmosphere via cooling towers.Stanley wrote: ↑23 Sep 2018, 03:54 ...and if a boiler had to be run anyway for process, the eventual cost of the leccy was about half price compared with the mains. Funnily enough, this point had been proved long before when manufacturers were being persuaded by the CEGB to ditch steam and go over to electric driving of looms.......

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

When Newton and I modified a diesel engine to run on gas and drive his alternator for leccy at home we piped the cooling water round the radiators in the house and it was very successful. I reckoned we were at over 85% efficiency and at the time I said to Newton that we should patent it. A few years later I saw a Fiat branded box outside a house in Oz, guess what, it was a small CHP plant!

I said yesterday that I had practical examples of how little steam engines used. Remember when we drew the fires after holiday pay had been paid out at Bancroft fully expecting all the weavers to leave early? Then there was a dispute about holiday pay and Jim Pollard told me we would have to relight the fires but I refused and simply ran on what steam there was in the boiler. We ran for two hours with no problem and no fires. Even I was surprised.

Worth reading Newton's account of the end of Pendle Street again.....

They were on oil, I’d run it before when it were a coal shop. I asked them how long their man was going to be off and the manager said oh happen two or three month we don’t know but we’re electrifying the looms and we’re hoping to finish by the July holidays. So I settled down to eight or ten weeks like you know, I thought he’ll be back will the lad soon as he gets reight. By gum though he didn’t get reight, he started with cancer and he died so I stopped on until the end. But the electrification like, I just weren’t interested in it at all and Miss Duckworth that were the old bosses daughter, unmarried daughter, comes down to see me one day happen some time around Easter time and she sat in the engine house with me a long while and she just says to me, excuse me Newton, I don’t want to appear ignorant but is this engine worn out, is it done like they’re saying it is? I said What! This engine’s better now than the day it were built in 1887. Whoever in the world is telling you that tale? Well she says, all these in’t mill have and this electrician and the manager. I said the engine never will be done Miss Duckworth as long as we’re about and you spend a bit on maintenance on it every year. Anyway it hasn’t had any for a lot of years and it doesn’t need it. A bit in’t boiler house perhaps but you’ll still have that to spend after your engine’s gone because you need steam for process and heating. Oh, she says, my father would spin round in his grave if he knew about this.

Anyhow, it didn’t stop the electrification and they kept electrifying them. I used to oil me air pump every dinnertime [in the cellar], I never struggled of a morning and I never struggled at night, I used to do me work during the day with me having to travel and all. I used to grease and oil me air pump at dinner time and I was right then until the day after. I used to walk down on me planks at dinnertime and they’d put this new cable down the engine house side in the cellar. It was a cable about two inches thick and naturally, I used to run me hand down it, it were like a hand rail as I were walking down the planks and I noticed it was just aired (warm). As it was getting on towards the end of June and they’d more looms going on to electric and I were getting less load on’t engine it were getting so as I couldn’t bide me hand on this cable at dinnertime. So I drew th’head electrician’s attention to it, I fetched him in. I said hey, this cable down the wall side, it’s getting blooming hot you know. Naaa, he says, it’s only thy heat that tha’s making in here, when we get this blooming old thing stopped it won’t get warm then. It’s all th’heat tha’art making with that blooming old engine. Blooming heck he says, that were the way he talked, blooming heck when we get that thing stopped and get shut of thee and that chap in the boiler house we’ll run this shop for nowt. We’ll run this shop for as much as it’s costing for yaa two in wages. I says will you. Anyhow, I’ll just go on a bit with this story.

Before I got me fireman, I only had a fireman for the last three weeks in the afternoon, I ran it meself from just after breakfast at t’morning. I used to let Tom go home, you know he were an old chap of about 67 or 68 and I used to let him go because he were doing me a good turn coming in early in the morning. They got a bit bothered about me being on me own all the time and they made arrangements in’t mill that somebody allus had to come down at brew time and have a natter with me and then go back after seeing that I was all right and hadn’t gone round the shafting or getten meself fast in’t engine which I had more bloody sense. Anyhow, one afternoon, th’big man came down to stop with me but he didn’t come while about twenty past four. He were a nice feller but he were no engineer, he were a weaving manager, he were over all the lot for Duckworths. I were sat in the boiler house reading comic cuts and pressing red and blue buttons on the board keeping us running. Now then Newton he says, oh won’t it make a difference to our bills when we get shut of the engine! Eh, I says, I’m not going to answer that, anyhow, have you got a bit of time? Oh aye he says I’m all straight now I can stop with you a bit and have a natter. Well I says it’s half past four and I have me jobs to do so I whipped up on to the top of the boilers and I shut the tape valves and all the heating off. I’d two boilers on line that’s all and just as I came down the iron ladder all four of me burners went Woof! Steam were up at 160. (Notice that what Newton had done was shut down all steam consumption except the engine.) So I stayed talking to him for a few minutes and then I says don’t go, I just want you to see how much you’re going to save when the engine stops cause now we’ve everything off but the engine. Reight ho he says. I says I want thee to stop here and count how many times them burners fire before I stop the engine at five o’clock and I think if I remember rightly we’d a 15psi dwell on those burners from 160, it came down to 145 before it fired up again.

So I goes up into the engine house and takes me jacket off and wiped round all the beds like I did every day, it were spotless even though I says it meself. All me beds all the way round, the floor, me cylinder tops and me covers and it were getting on to five to five so I sits down a minute or two and at five o’clock I stopped the engine. I waited while it stopped, put it in the reight shop for starting and went down into the boiler house and he’s still sat there. Now then Frank, how many times has them burners fired since I left you? I thought the feller were going to cry cause I looked up at the pressure gauges and they were on 150psi they were just getting ready for firing and we’d run half an hour with two boilers on and they’d never sparked and I knew damn well they wouldn’t. I thought the feller was going to cry, he said Tara Newton got up and walked out. As he was going I said that’s how much you’re going to save when you’ve getten all this bloody wire in the mill!

Anyhow, I finished at July holidays (1969) and before the year was out they were out of business and from what I heard Sam’s calculations for the electric cable were just half too bloody little and they were going to have to put a duplicate on underneath it and they couldn’t afford it and it finished ‘em. They’d three brand new boilers that were put in in 1926 when the engine was modernised and they went and electrified the place. I used to say to them in the old days, I’d say well, if I put an alternator on this engine you could make your own electric light and all because after respacing they had less looms and 500hp spare on the engine. It were 1400hp reckoned up properly was that engine. And that were at the end of Pendle Street.”

I said yesterday that I had practical examples of how little steam engines used. Remember when we drew the fires after holiday pay had been paid out at Bancroft fully expecting all the weavers to leave early? Then there was a dispute about holiday pay and Jim Pollard told me we would have to relight the fires but I refused and simply ran on what steam there was in the boiler. We ran for two hours with no problem and no fires. Even I was surprised.

Worth reading Newton's account of the end of Pendle Street again.....

They were on oil, I’d run it before when it were a coal shop. I asked them how long their man was going to be off and the manager said oh happen two or three month we don’t know but we’re electrifying the looms and we’re hoping to finish by the July holidays. So I settled down to eight or ten weeks like you know, I thought he’ll be back will the lad soon as he gets reight. By gum though he didn’t get reight, he started with cancer and he died so I stopped on until the end. But the electrification like, I just weren’t interested in it at all and Miss Duckworth that were the old bosses daughter, unmarried daughter, comes down to see me one day happen some time around Easter time and she sat in the engine house with me a long while and she just says to me, excuse me Newton, I don’t want to appear ignorant but is this engine worn out, is it done like they’re saying it is? I said What! This engine’s better now than the day it were built in 1887. Whoever in the world is telling you that tale? Well she says, all these in’t mill have and this electrician and the manager. I said the engine never will be done Miss Duckworth as long as we’re about and you spend a bit on maintenance on it every year. Anyway it hasn’t had any for a lot of years and it doesn’t need it. A bit in’t boiler house perhaps but you’ll still have that to spend after your engine’s gone because you need steam for process and heating. Oh, she says, my father would spin round in his grave if he knew about this.

Anyhow, it didn’t stop the electrification and they kept electrifying them. I used to oil me air pump every dinnertime [in the cellar], I never struggled of a morning and I never struggled at night, I used to do me work during the day with me having to travel and all. I used to grease and oil me air pump at dinner time and I was right then until the day after. I used to walk down on me planks at dinnertime and they’d put this new cable down the engine house side in the cellar. It was a cable about two inches thick and naturally, I used to run me hand down it, it were like a hand rail as I were walking down the planks and I noticed it was just aired (warm). As it was getting on towards the end of June and they’d more looms going on to electric and I were getting less load on’t engine it were getting so as I couldn’t bide me hand on this cable at dinnertime. So I drew th’head electrician’s attention to it, I fetched him in. I said hey, this cable down the wall side, it’s getting blooming hot you know. Naaa, he says, it’s only thy heat that tha’s making in here, when we get this blooming old thing stopped it won’t get warm then. It’s all th’heat tha’art making with that blooming old engine. Blooming heck he says, that were the way he talked, blooming heck when we get that thing stopped and get shut of thee and that chap in the boiler house we’ll run this shop for nowt. We’ll run this shop for as much as it’s costing for yaa two in wages. I says will you. Anyhow, I’ll just go on a bit with this story.

Before I got me fireman, I only had a fireman for the last three weeks in the afternoon, I ran it meself from just after breakfast at t’morning. I used to let Tom go home, you know he were an old chap of about 67 or 68 and I used to let him go because he were doing me a good turn coming in early in the morning. They got a bit bothered about me being on me own all the time and they made arrangements in’t mill that somebody allus had to come down at brew time and have a natter with me and then go back after seeing that I was all right and hadn’t gone round the shafting or getten meself fast in’t engine which I had more bloody sense. Anyhow, one afternoon, th’big man came down to stop with me but he didn’t come while about twenty past four. He were a nice feller but he were no engineer, he were a weaving manager, he were over all the lot for Duckworths. I were sat in the boiler house reading comic cuts and pressing red and blue buttons on the board keeping us running. Now then Newton he says, oh won’t it make a difference to our bills when we get shut of the engine! Eh, I says, I’m not going to answer that, anyhow, have you got a bit of time? Oh aye he says I’m all straight now I can stop with you a bit and have a natter. Well I says it’s half past four and I have me jobs to do so I whipped up on to the top of the boilers and I shut the tape valves and all the heating off. I’d two boilers on line that’s all and just as I came down the iron ladder all four of me burners went Woof! Steam were up at 160. (Notice that what Newton had done was shut down all steam consumption except the engine.) So I stayed talking to him for a few minutes and then I says don’t go, I just want you to see how much you’re going to save when the engine stops cause now we’ve everything off but the engine. Reight ho he says. I says I want thee to stop here and count how many times them burners fire before I stop the engine at five o’clock and I think if I remember rightly we’d a 15psi dwell on those burners from 160, it came down to 145 before it fired up again.

So I goes up into the engine house and takes me jacket off and wiped round all the beds like I did every day, it were spotless even though I says it meself. All me beds all the way round, the floor, me cylinder tops and me covers and it were getting on to five to five so I sits down a minute or two and at five o’clock I stopped the engine. I waited while it stopped, put it in the reight shop for starting and went down into the boiler house and he’s still sat there. Now then Frank, how many times has them burners fired since I left you? I thought the feller were going to cry cause I looked up at the pressure gauges and they were on 150psi they were just getting ready for firing and we’d run half an hour with two boilers on and they’d never sparked and I knew damn well they wouldn’t. I thought the feller was going to cry, he said Tara Newton got up and walked out. As he was going I said that’s how much you’re going to save when you’ve getten all this bloody wire in the mill!

Anyhow, I finished at July holidays (1969) and before the year was out they were out of business and from what I heard Sam’s calculations for the electric cable were just half too bloody little and they were going to have to put a duplicate on underneath it and they couldn’t afford it and it finished ‘em. They’d three brand new boilers that were put in in 1926 when the engine was modernised and they went and electrified the place. I used to say to them in the old days, I’d say well, if I put an alternator on this engine you could make your own electric light and all because after respacing they had less looms and 500hp spare on the engine. It were 1400hp reckoned up properly was that engine. And that were at the end of Pendle Street.”

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

One matter that comes up frequently is the reason why the cross compound engine was so popular when it took up far more room than a tandem and had no more power for the equivalent cylinder size, steam pressure and speed. The answer lies in the importance for the weaving shed of delivering a smooth drive to the shafting which increased production per loom. This isn't an important factor if you are driving something like a large alternator because the inertia of the spinning mass in the rotor tends to smooth out the delivery.

The problem with a tandem is that if you think about it a reciprocating engine has two peaks in its power delivery at each end of the stroke and because both pistons are on a common rod the output from both cylinders comes at exactly the same point each revolution of the flywheel. If you separate the cylinders and in effect create two separate engines you can set the LP crank at 90 degrees in front of the HP and instead of two points of power delivery you get four which makes the power output smoother. Don't ask me why the LP was set in front of the HP because I have never been able to puzzle that one out.

Surprisingly, some manufacturers went to the trouble of making a cross compound but set the cranks at either the same setting or at 180 degrees which defeated the advantage of separate engines as you still got only two power inputs. Apart from the unbalanced power output this tended to make the engine prone to throwing a rope off if started carelessly. Broughton Road Shed in Skipton was such a case and if you read Newton's transcripts in the LTP you'll find he was called to it and cured it by quartering it, moving the LP crank forward 90 degrees.

Bancroft was correctly quartered and as I proved to myself if you got the valve events right with just the right admission and exhaust points (the latter to control compression at the end of the stroke) and attended to greasing the ropes you could achieve a very smooth drive into the shed and become the weaver's friend because you raised their wages!

The problem with a tandem is that if you think about it a reciprocating engine has two peaks in its power delivery at each end of the stroke and because both pistons are on a common rod the output from both cylinders comes at exactly the same point each revolution of the flywheel. If you separate the cylinders and in effect create two separate engines you can set the LP crank at 90 degrees in front of the HP and instead of two points of power delivery you get four which makes the power output smoother. Don't ask me why the LP was set in front of the HP because I have never been able to puzzle that one out.

Surprisingly, some manufacturers went to the trouble of making a cross compound but set the cranks at either the same setting or at 180 degrees which defeated the advantage of separate engines as you still got only two power inputs. Apart from the unbalanced power output this tended to make the engine prone to throwing a rope off if started carelessly. Broughton Road Shed in Skipton was such a case and if you read Newton's transcripts in the LTP you'll find he was called to it and cured it by quartering it, moving the LP crank forward 90 degrees.

Bancroft was correctly quartered and as I proved to myself if you got the valve events right with just the right admission and exhaust points (the latter to control compression at the end of the stroke) and attended to greasing the ropes you could achieve a very smooth drive into the shed and become the weaver's friend because you raised their wages!

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

Another frequently asked question queries why steam engines don't have clutches and gear boxes like reciprocating internal combustion engines. The answer lies in torque characteristics, in simple terms the 'turning power' of the engine. If you run the torque curve for an IC engine on a dynamometer you will find that the curve starts at a very low level and rises as speed increases until it reaches a stable value which is the most economical speed to operate at. In a large diesel engine such as those installed in wagons it is less than 2,000rpm in most cases.

If you do the same exercise with a steam engine you'll find that the torque on the first stroke is the same in proportion to speed as it is at operating speed. This is because it depends on the steam pressure and the effective area of the piston. Starting from rest is no problem and doesn't need a clutch to allow the engine to develop full torque as the speed rises, the first stroke is powerful enough to overcame the inertia in the system if the engine is correctly sized. For the same reason it is almost impossible to 'stall' a steam engine. In an IC engine as the speed decreases so does the torque and so a gear box is needed. Of course even the power of a steam engine can be overcome but in a properly designed system with a known load this doesn't happen. Even a 12,000hp steam rolling mill engine with enormous variation in load has no problems.

This has disadvantages. One possibility was that in winter when the lubricant in shafting bearings has thickened overnight it was not unknown for the engine to shear off the crank pin when the steam valve was opened. In a large shafting system like Victoria Mill at Earby the barring engine was operated for as long as half an hour before the main engine attempted to start, the small steam engine was geared down so far that it could gently overcome the 'stiction' in the bearings. There is far less resistance in a cold bearing if it is only turned slowly. Half an hour of this reduced the inertia enough for the main engine to start on a very small opening of the throttle valve which didn't endanger the crank pin. The barring engine was designed so that the main engine could be applied while the shafting was turning slowly, as soon as the barring rack started to drive the small engine the gearing connecting it to the barring rack on the flywheel automatically dropped out and disengaged the drive.

In case you're wondering I have never run a turbine and don't know for certain how they coped with direct drive. However I know that they had a separate turning element designed to rotate the main drive and the the main turbine very slowly which aided warming of the turbine and I assume had the same effect as the barring engine on a conventional reciprocating engine.

If you do the same exercise with a steam engine you'll find that the torque on the first stroke is the same in proportion to speed as it is at operating speed. This is because it depends on the steam pressure and the effective area of the piston. Starting from rest is no problem and doesn't need a clutch to allow the engine to develop full torque as the speed rises, the first stroke is powerful enough to overcame the inertia in the system if the engine is correctly sized. For the same reason it is almost impossible to 'stall' a steam engine. In an IC engine as the speed decreases so does the torque and so a gear box is needed. Of course even the power of a steam engine can be overcome but in a properly designed system with a known load this doesn't happen. Even a 12,000hp steam rolling mill engine with enormous variation in load has no problems.

This has disadvantages. One possibility was that in winter when the lubricant in shafting bearings has thickened overnight it was not unknown for the engine to shear off the crank pin when the steam valve was opened. In a large shafting system like Victoria Mill at Earby the barring engine was operated for as long as half an hour before the main engine attempted to start, the small steam engine was geared down so far that it could gently overcome the 'stiction' in the bearings. There is far less resistance in a cold bearing if it is only turned slowly. Half an hour of this reduced the inertia enough for the main engine to start on a very small opening of the throttle valve which didn't endanger the crank pin. The barring engine was designed so that the main engine could be applied while the shafting was turning slowly, as soon as the barring rack started to drive the small engine the gearing connecting it to the barring rack on the flywheel automatically dropped out and disengaged the drive.

In case you're wondering I have never run a turbine and don't know for certain how they coped with direct drive. However I know that they had a separate turning element designed to rotate the main drive and the the main turbine very slowly which aided warming of the turbine and I assume had the same effect as the barring engine on a conventional reciprocating engine.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

Drives...... In the early days of prime movers such as waterwheels or occasionally horse gins (Gin is a corruption of 'engine' which in the early days meant any form of mechanical motion, not necessarily a prime mover) the drive from the power source to the driven machine was direct with no gearing or ropes. As watermills were increasingly used for driving textile mills in the 18th century gearing was used in the drive to increase the speed of rotation of the shafts used for the final drive. The first steam engines and many subsequent ones used gearing with a large jack wheel mounted on the side of the flywheel driving a smaller 'second motion' pinion on the shaft. The gearing was arranged to give the desired speed to the shafting, usually about 150rpm.In the later part of the 19th century grooves on the flywheel and second motion pulley carried cotton driving ropes which gave a quieter, vibration-fee and flexible drive. In England individual ropes were used but in the American version of the system an endless rope round all the grooves was often used. This never became popular in England because the use of an endless rope meant that the rope had to return from the final groove to the first passing across the other ropes and this almost always involved this return rope rubbing on some of the driving ropes causing friction and wear. If the rope failed it was more expensive to replace.

Cotton rope driving became very popular but in many cases in Room and Power mills it was not liked by the tenants because they argued they were losing out because of slippage which couldn't happen in a geared drive. Newton's opinion was that if the gear drive was modern steel machine cut gearing, often herring bone configuration, gear drives gave better service.

As in many walks of life there were variations. Some mills used large leather belts, often two side by side. These were made of multiple hides of course and multi-layered fastened together with copper rivets. Newton told a good story about a manufacturer who complained about all the joints as he thought he was getting an inferior belt. Newton asked him if he had ever see a cow 40 feet long....... Not all of these belts were made of leather. Balata Belting (LINK) was popular as it could be manufactured in any length.

Another variation which I have never seen was a woven steel belt. I believe they were common in the Heavy Woollen District round Huddersfield and Halifax. I know nothing about their qualities but can imagine they would be a fearsome thing if they frayed.....

If you want to know more about rope drives look for Kenton's lectures on cotton rope driving. He is a mine of information and his firm, Kenyon's at Dukinfield was one of the biggest manufacturers and suppliers not only of the ropes but the services of expert splicers for installing them.

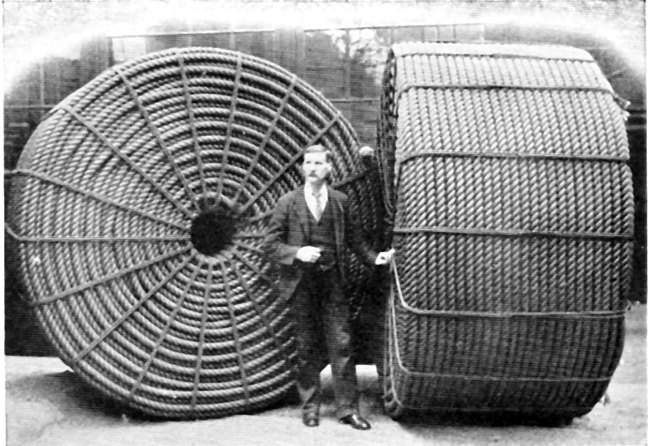

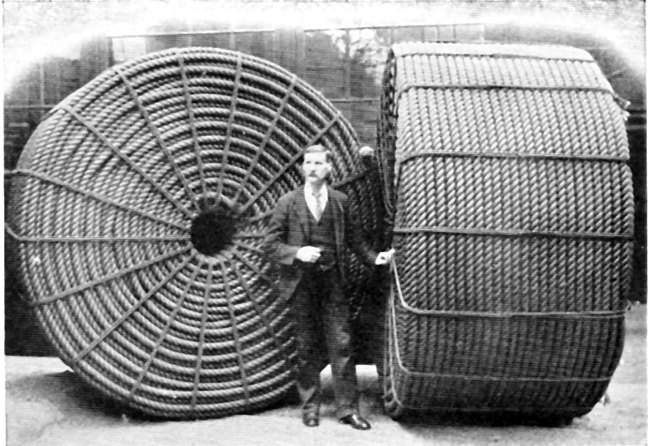

Cotton driving rope ready for export abroad.

Cotton rope driving became very popular but in many cases in Room and Power mills it was not liked by the tenants because they argued they were losing out because of slippage which couldn't happen in a geared drive. Newton's opinion was that if the gear drive was modern steel machine cut gearing, often herring bone configuration, gear drives gave better service.

As in many walks of life there were variations. Some mills used large leather belts, often two side by side. These were made of multiple hides of course and multi-layered fastened together with copper rivets. Newton told a good story about a manufacturer who complained about all the joints as he thought he was getting an inferior belt. Newton asked him if he had ever see a cow 40 feet long....... Not all of these belts were made of leather. Balata Belting (LINK) was popular as it could be manufactured in any length.

Another variation which I have never seen was a woven steel belt. I believe they were common in the Heavy Woollen District round Huddersfield and Halifax. I know nothing about their qualities but can imagine they would be a fearsome thing if they frayed.....

If you want to know more about rope drives look for Kenton's lectures on cotton rope driving. He is a mine of information and his firm, Kenyon's at Dukinfield was one of the biggest manufacturers and suppliers not only of the ropes but the services of expert splicers for installing them.

Cotton driving rope ready for export abroad.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Old age isn't for cissies!

-

Spinningweb

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

On the John & Edward Wood horizontal cross compound engine at the Brooklands Mill, (Mather Lane Mill No. 3) Leigh, Greater Manchester, to warn the engineer of a fraying rope, a metal rod spanning the flywheel had two bells on either end, which ever frayed rope lashed the rod would operate the bells.

You do not have the required permissions to view the files attached to this post.

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 104162

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

I have seen one device like that John, at Coldharbour Mill in the West Country. It was a light wooden rod that spanned the pit under the flywheel. One end was lodged in a recess and the other end on an alarm button exactly like a normal fire alarm, the difference being that instead of the glass retaining the alarm button in the open position, the rod served that purpose. If a rope started fraying it caught the rod and knocked it out triggering an alarm.

One of the delights of running an old artefact like the steam engine, especially in the latter days, was the number of casual visitors who turned up at the engine house door. No HS restrictions then, nobody from the management objected to them and I tried to make them all welcome. (This was easier with some than others but there you are.....)

I was particularly interested in the women who often accompanied their enthusiast partners who often had preconceived opinions and some even told me where I was going wrong! I always asked if they had come because they were interested or just following on. I got some interesting replies and often they said that they hadn't realised how satisfying the sight of a large steam engine quietly delivering power to the shaft was. Because they had no preconceived ideas they often made the best comments or asked the most perceptive questions. I watched one lady stand and watch the engine for about five minutes without moving so I asked her what she thought. She said that she thought that it was the most honest thing she had ever seen in her life and she loved it. I told her I agreed and thought she had put her finger on one of the chief virtues of these machines. You can watch an engine and see how it works, try doing that with an electric motor!

Another lady asked a very simple question, she asked me where the steam was. She told me she had expected to see steam and I explained that she had paid me a compliment because that was my aim, to keep the steam in the engine where it was doing some good. Leaks were a sign of wasted energy. I took her to one of the valves on the outside of the HP cylinder that I used for connecting my indicator, took the protective plug off and opened the valve. The result was of course a jet of high pressure steam at 140psi. Then I took her into the boiler house and showed her the same thing on the boiler. Such a simple direct question and it allowed an explanation that went to the root of how we made and used steam.

The key to steam tightness is often all about how good the gland packings are on valves. The metallic packings on the piston rods looked after themselves and were all in good nick. Gland packing with asbestos string impregnated with graphite and oil could be very efficient as long as it was occasionally renewed as over time it bakes hard. The mistake in that case is to simply tighten the gland nut which will stop the leak temporarily but in the process puts pressure on the shank of the valve and wears it to the point where no matter what you do it will always leak. The same applies particularly to soft packings on piston rods.

There was one form of packing that defeated many engineers, this was the asbestos packing in the valve cocks on the water gauge pipework. This wasn't normal string packing but a special granulated compound of asbestos fibre, graphite, and a small amount of a rubber based compound. It is called 'Indurated Asbestos'. The way it works is that the cock is constructed with four passages machined in the body of the valve where the conical plug fits. You cleaned the old packing out of these and then with the conical plug in place you forced the compound down into these grooves with a specially shaped punch with a flat end that exactly fitted to space. You hammered the compound in place until you were sure you had it filled with tightly packed compound. Then put the top on the valve, which can be screwed down on the packing where it bulged above the grooves but at this point only loosely. Then you completed the job by baking the packing by allowing steam to leak through the plug at at least 50psi. This vulcanises the rubber in the compound and the plug cock will loosen and perhaps leak slightly. When you are sure it has set, screw the top down slightly until the leakage stops. Done properly this packing will last for many years.

I have an idea that Indurated Asbestos compound is no longer made. If you need a valve packing, bring it to me. I still have some in stock! (And know how to use it)

One of the delights of running an old artefact like the steam engine, especially in the latter days, was the number of casual visitors who turned up at the engine house door. No HS restrictions then, nobody from the management objected to them and I tried to make them all welcome. (This was easier with some than others but there you are.....)

I was particularly interested in the women who often accompanied their enthusiast partners who often had preconceived opinions and some even told me where I was going wrong! I always asked if they had come because they were interested or just following on. I got some interesting replies and often they said that they hadn't realised how satisfying the sight of a large steam engine quietly delivering power to the shaft was. Because they had no preconceived ideas they often made the best comments or asked the most perceptive questions. I watched one lady stand and watch the engine for about five minutes without moving so I asked her what she thought. She said that she thought that it was the most honest thing she had ever seen in her life and she loved it. I told her I agreed and thought she had put her finger on one of the chief virtues of these machines. You can watch an engine and see how it works, try doing that with an electric motor!