In 1841/42 John Petrie, engine maker of Whitehall Street, Rochdale, built a 20nhp beam engine for John Hurst at Whitelees Mill, Littleborough at a cost of £650. It ran successfully under various owners until 1942 and, apart from a steel flyshaft replacing the original cast iron one, was never modified. In 1957 the Co-operative Wholesale Society were owners of the mill which was weaving blankets at the time. They wanted the engine out to give room for expansion and Holcroft Limited of Rochdale who’s foundry was on the site of the original Petrie works offered to build an engine house and erect the engine there as a monument to Rochdale engineering. It was powered by an electric motor and could be run for the public on special occasions. The engine house was glass-fronted and Rochdalians got used to seeing the engine sat there on the side of the road.

Things remained like this until 1988 when the owners of the foundry, Reynolds Gears, decided to close the works and re-develop the site as a retail barn. The engine would have to go. It was not scheduled or protected in any way and therefore was up for grabs. The people building the Wheatsheaf Centre heard about it and decided they would like it for their showpiece. It was at this point that someone told them they ought to talk to me before they made any irrevocable decisions.

I went to meet them and pointed out that they couldn’t just plonk it on the floor and put an electric motor on it. The first problem was getting it out, it was next to the road but as this was a busy major route it made it inaccessible from that side. Further, they would need a pit twelve feet deep underneath it and then a clear thirty feet above. It soon became clear to them that this was a bit more than they had bargained for. They asked me to come up with alternatives and I eventually found them a large wood saw built in Rochdale by Tommy Robinsons, a deep well pump headgear and a small steam engine to couple up to the pump. They settled on this and I arranged for the whole lot to be refurbished and installed by the Rochdale Apprentice Training School. All this took time but was completely successful.

As soon as I knew that the Co-op weren’t going to take the engine I had a word with Peter Dawson and we sketched out a preliminary scheme for installing the engine in the bare space in the boiler house where the other Lancashire boilers had been. I also approached the Science Museum and English Heritage and told them what I wanted to do and asked their opinion.

At this point I should explain that English Heritage do not consider themselves competent to make judgements about machinery. They rely on the opinion of the Science Museum who, though nominally the minor partner in this process, actually hold ultimate power on funding decisions. I was astounded when they turned the idea down on the grounds it would dilute the ‘purity of the concept’ at Ellenroad. I couldn’t understand their reasoning and no matter how I pressed them couldn’t get them to reconsider. I was baffled.

Then I got a letter from David Sekers at Quarry Bank informing me that he had got the Whitelees Engine and was going to install it at Styal. The letter included the phrase ‘Ha Ha, we’ve got it!’ I also found that David had used a selective quotation out of a private letter which he had obtained as supporting evidence for his case to move the engine. All this bothered me. For a start there was no need for supporting evidence as the engine wasn’t protected in any way by the Ancient Monument Acts. Secondly I knew there were close links between Quarry Bank and the Science Museum and I can’t believe that David would consider installing the engine without informing them first. It all smelt to me of discussions in closed rooms and a fait accompli. I have to admit I lost my temper and I’m not ashamed of it. I wrote David a controlled but venomous letter and copied this to the Science Museum and English Heritage. I heard later that photocopies of it had been put on various notice boards in English Heritage and had caused some amusement.

My next move was to contact John Pierce and inform him that Rochdale was being burgled and what was he going to do about it. My case was that the engine had been brought back to the town as an example of Rochdale engineering and, even though nothing was ever committed to paper, it was obvious that the Co-op and Holcrofts had intended Rochdale to be its final home. Further, I wasn’t at all sure that Reynolds actually owned the engine or had the right to give it away. I had an idea that if the matter was traced back to its roots, the Co-operative Wholesale Society were still the legal owners of the engine. John didn’t let me down, he went off and did what he was best at, I was never consulted and to this day I don’t know what he did but the upshot was that Trevor Grice, the CEO of Reynolds informed David Sekers that the deal was off. I was asked to come up with a scheme to install the engine in a glass case outside the Town Hall but I got the impression that apart from the practicalities of this scheme, it was never seen as a viable alternative to installing it at Ellenroad in steam. I was also led to understand that in any dispute with any of the funding bodies, I would most likely get backing from the council. None of this was on paper but it was right up my street.

In January 1989 I did a report for the council that shot the glass case down and then I made a convincing case for installing it at Ellenroad in steam. The next I heard was that Reynolds would give the engine to the Trust and if we could get it out within ten working days they would give us approximately £30,000 as a donation. The exact amount depended on how successful they were in reclaiming tax on the donation. At this point I raised the matter of the ownership of the engine. I pointed out that there were three levels of proof of ownership in law. These were possession, title and provenance. Possession was with Reynolds, I suspected title was with the Co-op and they would have records of purchase that could prove provenance, or in other words, the audit trail. I said that what we needed was a letter from the Co-op which acknowledged that we had the engine and devolved any residual rights they had in it to us. In other words we would have all three elements of ownership and this could never be questioned. I went for this because in my years with museums I have come across so many cases where a museum had artefacts which they couldn’t actually prove belonged to them. John Pierce agreed with me and set in motion the machinery for getting us the documentation from the Co-op. Having done this, I could get going, I was, to put it mildly, in my element. I went down, had a look at the rabbit, arranged for access and went away to lay my plans.

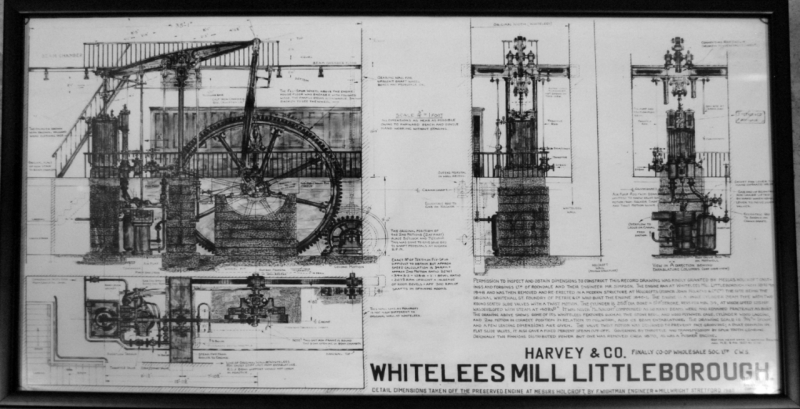

Frank Wightman's drawing of the engine at Littleborough. In the end this was the only drawing I had and this caused problems.